Since last fall, a new player has burst into the heart of the gambling landscape — while declaring itself not gambling. Prediction markets, such as Kalshi and Crypto.com, began offering consumers the opportunity to place de facto sports bets at the end of 2024 and have continued to expand their menus since.

Their rise has the regulated industry in a tizzy. In particular, Kalshi’s arrival has brought tribes across the U.S. together in a united effort to defend sovereignty and the right to gaming exclusivity.

Prediction platforms are not currently held to the same gambling-centric standards that betting companies regulated by states and tribal councils are. They do not pay state taxes or have to necessarily adhere to often stringent responsible gambling, anti-money laundering, and other standards, although they are proactively and preemptively taking some of those steps. And as of now, the prediction markets owning a Designated Contract Market (DCM) license with the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) have the ability to transact with clients anywhere in the U.S.

As the U.S. tribes, states, and gaming stakeholders become increasingly aggressive about keeping federally regulated prediction markets off their turf, it has often been the tribes themselves that have taken the lead. Indian Country has filed several amicus briefs arguing that Kalshi does not have the right to operate on tribal land, and is educating its own at conferences, through webinars, and at grass-roots meetings.

The National Indian Gaming Commission (NIGC) — an independent federal agency that regulates gaming on Indian lands — could potentially quarterback the effort or serve as a rallying point for tribes. The agency so far is “actively engaged in monitoring the discussion” and has been since well before any tribe reached out, Chief of Staff Dustin Thomas told InGame. Though it has not issued any statements or initiated any events, Thomas said his agency participated in a legislative summit sponsored by Indian Gaming Association (IGA) and a meeting of tribal leaders in Washington, D.C. in June, and has accepted every request and meeting from tribes.

Among its duties, the NIGC interprets and implements the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA). The agency, per its website, has “approval authority over management contracts and tribal gaming ordinances, and mandates the Commission to provide training and technical assistance, and enforcement when necessary. Congress also vested the Commission with broad authority to issue regulations in furtherance of the purposes of the IGRA.”

InGame talked to more than half a dozen people, many of whom requested anonymity, to assess why the NIGC hasn’t taken a more central role in the fight against prediction markets. The answer appears to stem, in part, from politics, which has left the agency in flux in terms of leadership and staffing.

It also moved offices earlier this year, after its lease expired. The staff — both overall and in-office — has evolved over time, as well. The NIGC, while a government agency, is funded directly by Indian Country, not tax dollars.

As of today, the NIGC is still without a Senate-appointed chair, but there are many ways it could become more involved or take a point position in Indian Country’s fight against prediction markets.

NIGC an agency without an appointed leader

In July 2024, the U.S. Senate received a nomination for Patrice Kunesh to replace Sequoyah Simermeyer as the head of the NIGC. Simermeyer, who had served beyond his three-year term, resigned from the agency in February 2024 to take a position at FanDuel. Indian Country considered Kunesh, a Standing Rock Lakota descendant, commissioner of the Administration for Native Americans, and former counsel for Connecticut’s Mashantucket Pequot Tribe, an agreeable choice for the job.

She went through a confirmation hearing in September, and Nov. 20, 2024 — 15 days after now President Donald Trump won his second term — the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs sent a favorable recommendation for Kunesh to the Senate floor. A vote never happened, and during the transition from then President Joe Biden to Trump, Kunesh’s nomination was “returned to the President.”

Seventeen months after Simermeyer resigned, the NIGC — the federal voice of Indian Country — is still without an appointed chair. Commissioner Sharon Avery is currently the acting chair, and has been for more than a year. Up until June 16, it appeared as if another Simermeyer would ultimately take the helm — Sequoyah’s brother, John, was nominated by the Trump administration in April. But last month, his nomination was withdrawn.

The move left at least some to wonder if leaving the position unfilled is the end game for the Trump administration.

“Trump has fired almost everybody from independent agencies,” IGA Executive Director Jason Giles told InGame. “He’s neutered a lot of these independent agencies. Maybe part of the plan is not to fill this. They are neutered and can’t take any action.”

Through the turmoil at the top, Avery, an enrolled member of Michigan’s Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe, and Commissioner Jeannie Hovland, a Santee Dakota Sioux tribal member, have kept the agency running.

Giles said the “Biden administration left us in a really bad place.”

Indian Country files amicus briefs

In the last month, Indian Country has banded together to submit amicus briefs in cases brought by Kalshi in New Jersey and Maryland. More than 65 tribes and tribal groups signed the New Jersey brief, which laid out a clear argument about how allowing sports event contracts — tantamount to sports betting by another name — by companies not licensed or regulated by states is a direct violation of IGRA.

That 1988 law, at its core, allows federally recognized tribes to negotiate with states for exclusivity for Class III gaming on their own lands. In some states, including California, Florida, Oklahoma, Minnesota, and Washington, tribes have also entered into compacts to modify or extend that exclusivity. The best example is Florida, where the Seminole Tribe and the state compacted to allow the tribe to exclusively offer digital sports betting (and eventually online casino) throughout the state. They can do so because the compact includes “deemed” language, which says that bets are considered placed where received. And if a bet is received at a tribal server, then it is considered to have been placed on Indian lands.

Outside of Florida, tribes in Arizona, Connecticut, and Michigan gave up exclusivity and agreed to regulatory oversight by the states in order to offer online sports betting. Online betting is not legal in California, Oklahoma, Minnesota, or Washington, and tribes in those states are aiming for Seminole-style exclusivity.

The rise of prediction markets has also created strange bedfellows. The day after a tribal coalition filed its amicus brief in the New Jersey case, an amicus brief signed by 34 attorneys general followed. The attorneys general made many of the same arguments as the tribes, including that prediction markets encroach on sovereignty.

Two agencies operating without permanent bosses

Because they operate under the purview of the CFTC, prediction markets are currently legal across the U.S. But even under the most basic interpretation of IGRA, the companies running those platforms are violating federal law by offering their product on tribal land, which is sovereign.

No tribe yet has yet sent Kalshi or its peers a cease-and-desist or other kind of directive to get off of a reservation. The NIGC so far has not made any public statements or taken clear action with regard to prediction markets. It seems highly unlikely that the agency would sue the CFTC — both are government agencies represented by the Department of Justice. But according to Ryan Rodenberg, a Florida State University professor who has been following the Kalshi litigation closely, it’s not unprecedented for one government agency to sue another.

“Lawsuits pitting one independent executive branch agency against another federal agency are rare,” he said. “However, there is precedent supporting the justiciability of such litigation, including a dispute five years ago involving the U.S. Postal Service.”

With regard to filing amicus briefs, the NIGC’s Thomas said, “Out of respect for the ongoing litigation, I cannot comment.”

Both the CFTC and NIGC are currently operating without Senate-appointed chairs. Brian Quintenz — the Kalshi board member Trump nominated to head the CFTC — had a confirmation hearing June 10, but has not yet been voted on by the full Senate.

Who the next NIGC nominee will be, or when they’ll be nominated, isn’t known.

What could the NIGC do to move itself into the “quarterback” position and take point on this fight? Or is that even where the agency should be? At the CFTC, which will be down to a single commissioner this month, the agency called and then canceled a comprehensive conference call on the subject. When it later settled on a tribes-only call, the takeaway was that the agency — under its acting chair who said the CFTC has never denied a new market — would not impede Kalshi. It was also indicated that the agency would not take a risk before a Senate-appointed chair was confirmed.

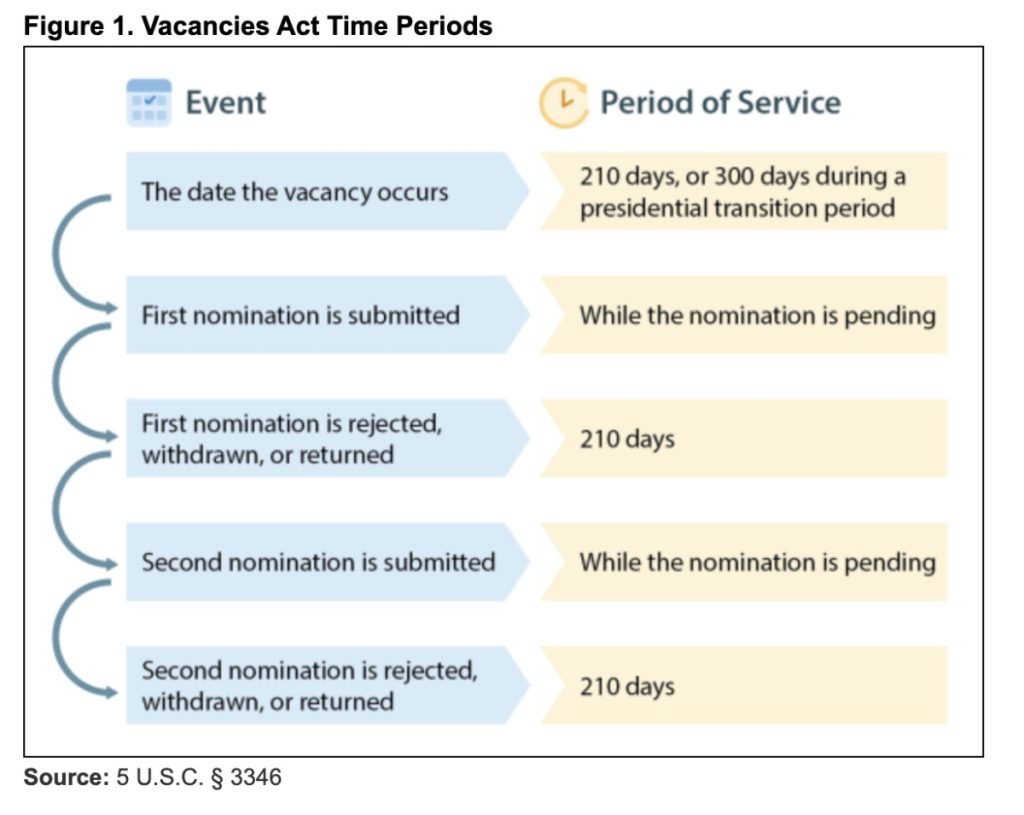

The same could be true at the NIGC, or any federal agency. A person in a temporary position seems less likely to take a risky posture until they knows a job is theirs. That said, according to the Federal Vacancies Act, acting chairs have most, if not all, of the powers of Senate-confirmed chairs. How long an acting chair can be in place is unclear — according to the Vacancies Act, the timing of an acting chair position starts when a chairmanship is vacated, and is set at 210 days. That can be extended if a nomination is made. That said, the law outlines extensions during confirmation periods for first or second nominees, but does not address what happens if two nominees are rejected or withdrawn, which is the current situation.

What the NIGC could do

Regardless of who is in charge, the NIGC does have some options to get more publicly involved, sources told InGame. That said, sources said the agency is wise to take its time, be “deliberate,” and consider all the consequences. Given that Kalshi is already in court with multiple states, the NIGC would have to do its homework to make sure whatever it does would stand up in court.

“We want the NIGC to assert their regulatory authority, and let gaming companies know that all gaming taking place on Indian lands is under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act,” the IGA’s Giles said. “If you are gambling on tribal land and are not regulated by the NIGC, then it is not authorized by a tribal-state compact, so you are violating the law.”

Here’s a look at some avenues available to the NIGC:

Make a statement

Writing an open letter or making a public-relations statement would not have any teeth, but the NIGC could get its thoughts on exclusivity and tribal sovereignty into the public domain. The agency could write a strongly worded letter saying that allowing prediction markets to operate on tribal lands is a clear violation of IGRA and won’t be tolerated. Such a letter or document could be posted on the NIGC website, sent to the offending party (Kalshi), or sent out as a press release.

That could set the stage for individual tribes to send cease-and-desist letters, or for tribal gaming councils to take other action.

Issue a ‘letter of concern’ and/or ‘notice of violation’

A chair may issue a letter of concern ahead of taking enforcement action — such a letter constitutes technical assistance that may or may not result in enforcement action, according to the NIGC.

If an issue is not rectified following a letter of concern, the NIGC may then issue a notice of violation. These types of letters outline the issue, explain how to rectify a situation, and may include a deadline. These types of letters only apply to gaming tribes. For states, the first step in enforcement action has been cease-and-desist letters sent to Kalshi. In three states — Maryland, Nevada, and New Jersey — Kalshi’s response has been to file a lawsuit. The Arizona regulator has also sent a cease-and-desist, and filed an objection with the CFTC, but Kalshi so far has not filed a lawsuit against that state.

Invite tribes to a discussion

The CFTC ultimately held a tribal roundtable discussion with representatives from eight tribes or tribal groups. The NIGC could do the same, leading tribes in a conversation about their concerns, potential courses of action, and the like. Such a conversation could be the foundation on which tribes across the country could further refine their positions and arguments.

Local and regional outreach

The NIGC doesn’t just have an office in Washington, D.C. It has eight regional offices, including three in the west, two in Oklahoma, and one in Minnesota. Tribes often have most of their contact with the regional offices rather than the D.C. national office, and the NIGC could do outreach and educational programs through those offices. Indian Country has been doing its own more informal education through Victor Rocha’s The New Normal webinar series, at conferences, and at in-state tribal meetings.

The NIGC also already offers training sessions on everything from anti-money laundering to compliance to environmental and health issues. It could offer a similar program at the national or regional level or via webinar.

What tribes can ask the NIGC to do

In addition to the NIGC taking independent action on the issue of prediction markets and tribal exclusivity and sovereignty, tribes can ask the agency to get involved in several different ways.

Issue a legal opinion

If a tribe or tribal group asks the NIGC to offer a legal opinion on the legality of prediction markets being available either on a reservation or in a state, the agency could craft one. Such an opinion would be like the one expected from California Attorney General Rob Bonta’s office this week regarding daily fantasy sports — it would be just that, an opinion, not a new law or framework. But it would give those trying to banish Kalshi another tool to use.

IGRA allows Indian tribes in the U.S. exclusivity to Class III gaming. The NIGC currently defines Class III gaming as “baccarat, chemin de fer, blackjack, slot machines, and electronic or electromechanical facsimiles of any game of chance.” But a tribe can request a more specific definition or legal opinion on any game.

Define what legal sports betting is

The NIGC does not currently appear to have a definition just for legal sports betting. An event contract on the outcome of a sporting event is, as many in the industry have pointed out, a reasonable facsimile of legal sports betting in that bettors wager on the outcome of an event. Kalshi itself has at times advertised that it offers sports betting.

But the guts of what Kalshi offers is dramatically different than the guts of legal sports betting regulated by states and tribal councils. A tribe or tribal group could ask the NIGC for an updated definition.

Offer education, support

While the NIGC could choose on its own to offer educational sessions about prediction markets and the threat to sovereignty, tribes and tribal groups are also at liberty to ask the agency to have such sessions. These could be offered digitally, or through regional offices.

As Indian Country continues to fight, the NIGC has options should it choose to ramp up involvement. But at the heart of the fight at all levels is this: Only gaming operators licensed by Indian Country can operate on reservations.

“For any gaming company that is operating on tribal land, they have to submit to background checks to the NIGC,” the IGA’s Giles said. “Then, if they continue to allow people to use their product and enlist and sign up customers, you’re getting into more and more violations. You cannot set up gambling operations on a reservation without NIGC approval.”