A state court in Massachusetts has granted an injunction that will block Kalshi from operating in the commonwealth beginning Friday.

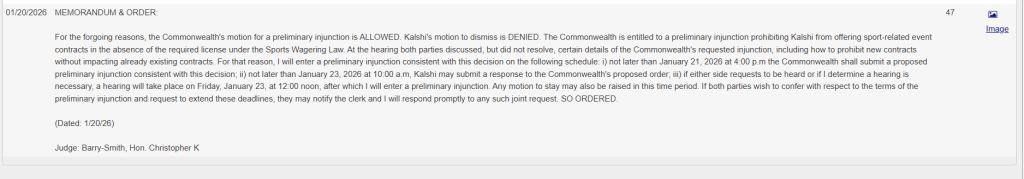

Suffolk County Superior Court Judge Christopher Barry-Smith handed down the order Tuesday, citing arguments that resembled prior decisions against the prediction market in federal lawsuits.

MA-decisionHowever, details of the injunction appear to still need to be hashed out.

Barry-Smith’s order notes that in a hearing last month, the parties “discussed, but did not resolve, certain details of the Commonwealth’s requested injunction, including how to prohibit new contracts without impacting already existing contracts.”

As a result, Massachusetts will submit a new proposed injunction to the court Wednesday, with the aim of coming to an agreement on how to avoid impacting contracts that have already been bought. Kalshi may then respond to that proposal by Friday morning. A hearing will be held Friday at noon, after which the injunction is set to go into effect. During that hearing, Kalshi may call for a motion to stay, which would pause the injunction’s entry into force.

Andrew Kim, a partner at Goodwin Law who has been following the various lawsuits concerning prediction markets but is not directly involved, noted that the pattern in which the state proposes an order is common in state-level lawsuits.

Only state lawsuit on Kalshi legality

The case is currently the only lawsuit resulting from a state suing Kalshi, and the only Kalshi-vs.-state lawsuit taking place in a state court. However, Kalshi is not the only prediction market subject to a state-level lawsuit on its legality. On Friday, the Nevada Gaming Control Board sued Kalshi’s rival Polymarket in Carson City District Court, seeking a declaration and injunction “to stop Polymarket from offering unlicensed wagering in violation of Nevada law.”

While the prediction market is engaged in lawsuits with several other states, in all of those cases, Kalshi sued the state after receiving a cease-and–desist order.

In this case, Massachusetts Attorney General Andrea Campbell sued Kalshi in September, arguing the platform was in violation of Massachusetts’ sports wagering laws.

Kalshi attempted to have the lawsuit moved to federal court, but a judge rejected its bid to do so in October.

Arguments similar in MD federal lawsuit

Despite the different setting, the arguments involved in the case are similar to those made in federal cases. As usual, Kalshi argued that, because it is regulated by the federal Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), state wagering laws do not apply. Instead, it argued, those laws are preempted by the federal Commodity Exchange Act (CEA).

However, Barry-Smith rejected that idea.

“In its opposition to the Commonwealth’s motion, Kalshi does not argue that its sports-related event contracts do not meet the definition of sports wagering in the Commonwealth,” he wrote. “Neither does it challenge the Commonwealth’s assertion that it is operating in Massachusetts without a license.

“Rather, consistent with its litigation strategy in other states that have challenged its operation, Kalshi argues that the Commonwealth’s attempt to regulate its exchange through the state’s Sports Wagering Law is preempted by federal law. As explained below, I disagree.”

In focusing on the question of preemption itself, Barry-Smith’s decision was similar to a decision made in a federal lawsuit about Kalshi’s operations in Maryland, where a judge in August denied Kalshi an injunction that would have allowed it to keep operating in the state.

Maryland is one of two other states where Kalshi has faced a significant legal setback. In Nevada, a judge dissolved an order that he had previously granted to Kalshi, but that decision rested more on whether Kalshi’s sports contracts could be accurately defined as “swaps,” a type of financial instrument traditionally used for hedging risk, and therefore whether they fell under the CEA at all.

In both Maryland and Nevada, Kalshi appealed the decisions that went against the business, and it remains active in both states while its cases are being heard in the appeals circuit.

Like the judge in the Maryland case, Barry-Smith said that the CEA did indeed preempt state law, but only in the field of futures trading. The preemption, he said, did not extend to state wagering laws.

“While it would make sense for Congress to displace a state’s targeted attempt to regulate a derivative market, for example, or to clarify the roles of separate federal agencies [..] that logic does not suggest Congress intended to displace traditional state police powers, such as gambling regulation – particularly in the absence of the express language so stating,” he wrote.

The judge cited a Ninth Circuit case in which the court ruled that federal aviation safety laws did not preempt state-level laws around personal injury suits.

“That none of the CEA preemption cases Kalshi cites in support of its exclusive jurisdiction argument concern state gambling regulation, or the CEA’s preemption of other equivalent historical state police powers, speaks to its overbroad view of relevant preemptory field,” Barry-Smith added.

He also noted that the CEA does specifically say that state gaming laws are preempted for certain types of contracts, but Kalshi’s contracts do not fall under any of the types of contract listed in that passage. The state of Maryland previously argued that this passage was proof that Kalshi’s contracts were not immune from state wagering laws.

Judge: Kalshi can follow CEA and state law

Kalshi has also argued that state wagering laws must be preempted because it would be impossible to comply with both those laws and the CEA, and in cases like that, the federal law takes precedence.

However, like federal judges, Barry-Smith rejected this idea, arguing that while it may be inconvenient to follow both laws, it would not be impossible.

“The Sports Wagering Law is an exercise of traditional state police power,” he wrote. “It imposes an additional regulatory burden on an event contract platform that seeks to offer sports related event contracts, in service of the public health. It is not a competing attempt to regulate derivatives markets, or an outright ban on event contracts in the state.

“The undercurrent to Kalshi’s argument is that it would prefer to avoid the burden and expense of state licensure. That is an insufficient reason, however, to overcome the strong presumption against conflict preemption in this case.”

Kalshi’s hardship ‘is of its own making’

Outside of the merits of the case itself, Barry-Smith determined that issuing an injunction was within the public interest. He said he was not convinced by the argument that the injunction would cause harm to Kalshi or its users, because in his view it is harm of the exchange’s own making.

“Kalshi knowingly proceeded in Massachusetts and other states that require sports wagering entities to be licensed, even after the CFTC warned it to be cautious in light of ongoing state enforcement efforts,” he wrote.

“Thus, any hardship it faces in removing its non-compliant Massachusetts offerings is of its own making. There can be little question that Kalshi well understood that its business model-especially once it began offering bets on sporting events-came into direct conflict with state enforcement regimes; Kalshi chose to take that risk head-on.”

‘Dynamic preemption’ previously mulled

During the December hearing, Barry-Smith provided more insight on how he viewed the case. Barry-Smith said that in his view, the question at the heart of the case was whether an issue can “grow into preemption.” By this, he meant that he believed it would be “absurd” to think Congress originally intended for the CEA to overrule state wagering laws, but he felt that it was possible that the nationwide expansion of sports betting since the repeal of PASPA had made the idea less absurd.

During that hearing, Barry-Smith also mulled whether sports event contracts truly met the definition of a “swap” – a type of financial instrument traditionally used for hedging. States have argued that even if the CEA overrules state law, that would not apply to Kalshi’s contracts because they don’t meet the definition of a swap.

Unlike judges in previous cases, Barry-Smith looked not just at the formal definition of a swap in the CEA but also an introduction to the section of the law that covers swaps. During that introduction, swaps are described as, “a means for managing and assuming price risks, discovering prices, or disseminating pricing information through trading in liquid, fair and financially secure trading facilities.”

Barry-Smith said he didn’t believe sports contracts would fall under that description.

Will Kalshi appeal?

Spokespeople for Kalshi declined to comment or reveal whether the business will appeal.

Despite legal setbacks in Maryland and Nevada, Kalshi has yet to shut off access in any part of the U.S. so far. The Massachusetts order will come into effect just before the NFL’s Conference Championship games. The New England Patriots will be playing for a spot in the Super Bowl on Sunday, in a game likely to draw particular interest in Massachusetts.

Any possible appeal would be made to the Massachusetts Appeals Court, but the Supreme Judicial Court — the highest court in Massachusetts — could have the power to take the case directly without it being heard by the appeals court.