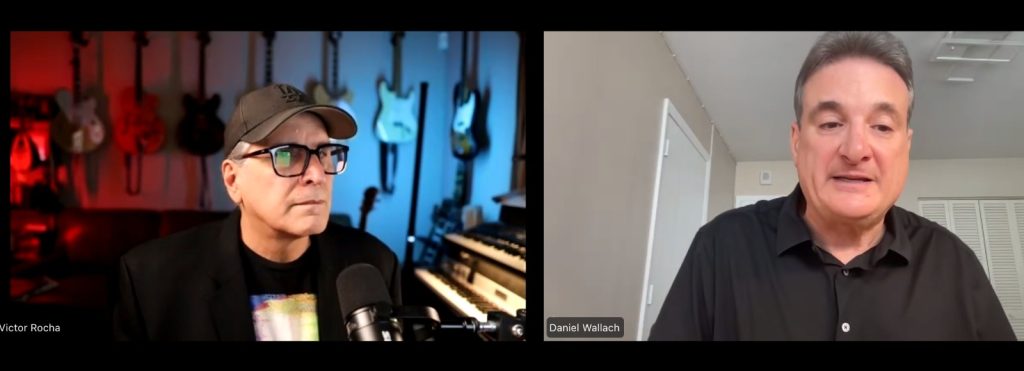

Gaming attorney Daniel Wallach didn’t discriminate during an industry webcast Wednesday.

In the ongoing battle between state-regulated sports betting stakeholders and prediction markets, he called out federal courts — in some cases naming the judges — state regulators, tribal gaming regulators, and Kalshi. The road to the Supreme Court or a congressional decision about what and how prediction markets should be regulated, he said, has been slowed by all parties.

Any lasting or final decision, he told host Victor Rocha on the “New Normal: Why Prediction Markets Are Facing Their Biggest Legal Test Yet,” likely won’t come until the end of 2027 at the earliest. And the decision on whether or not prediction markets can continue to offer sports event contracts won’t come from state regulators or lawmakers, it will come from either the Supreme Court or Congress.

“These preliminary victories by Kalshi have all but ensured the elasticity of sports prediction markets at least through the end of calendar 2027 until the issue is decided by the courts or Congress,” Wallach said. “There is nothing any state legislature can do about this. There is nothing the CFTC (Commodity Futures Trading Commission) can do. They can place their thumb on the scale, but ultimately, this is an issue to be decided by the courts, and if the courts rule that federal laws do not preempt state sports gaming laws, it’s game over unless Congress intervenes and amends the Commodities Exchange Act (CEA) or passes a federal sports gambling regime that provides some legal cover for sports prediction markets.”

Cease-and-desist letters were missteps

Wallach walked Rocha through the issues that have slowed the process — in particular, state regulators sending cease-and-desist letters to Kalshi and other prediction markets. He said those letters invited Kalshi to sue in federal court, and allowed the company to focus on the question of whether or not sports event markets should be considered swaps, and as such would not fall under state gambling regulation.

The paradigm began to change, he said with a ruling in Maryland, where the focus became congressional intent — i.e. was it Congress’ intent that federal law displace state gaming laws? If the answer is no, he said, it’s “game over” for sports event contracts on prediction markets.

With a dozen states now in court — some state, but most federal — with Kalshi, Wallach said that the last six rulings have been in favor of state regulation, and he expects that trend to continue. He pointed to upcoming appellate court activity in the Third, Fourth, and Ninth Circuits as “critical.”

District court decisions have been appealed to each of those courts. The Dodd-Frank Act is at the center of those cases, though Wallach said that Congress in 2010 did not explicitly ban gaming on derivatives exchanges, which he called a “mistake.” Rather, Congress left the decision about how to handle gaming up to the CFTC, but he said that via the overturning of the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act in 2018 and other decisions, the Supreme Court has already made it clear that gambling is a states’ rights issue.

Weight of IGRA hangs in balance

Another key issue that could be decided in the coming months is how much standing the nation’s tribes will have in the fight against prediction markets. Tribes in California and Wisconsin have sued Kalshi to keep the platform off their lands. In a district court ruling in San Francisco last fall, however, Judge Jacqueline Scott Corley found that “Kalshi trades on Indian lands aren’t gaming activity.”

Wallach called the decision “nonsensical” and explained that for tribes, it’s critical to get a circuit court decision that re-establishes the idea that the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) “covers wagering that begins on tribal lands, even if it is ultimately received outside of tribal lands.” The three tribes — Blue Lake Rancheria, Chicken Ranch Rancheria of the Me-Wuk Indians, and Picayune Rancheria of the Chukchansi Indians — have appealed to the Ninth Circuit.

“The outcome of the tribal appeal will either resurrect IGRA as a federal law that encompasses internet wagering, or it will slam the door shut, at least for now, on the ability of tribes to sue Kalshi directly in federal court. That is a vitally important case.”

Kalshi’s geofencing argument moot

Moving away from regulators, Wallach said actions by other prediction markets, including Crypto.com, DraftKings, and FanDuel, are hurting one of Kalshi’s initial arguments regarding federal vs. state regulation. In multiple cases, Kalshi argued that the cost of geofencing out certain jurisdictions would be prohibitively expensive and cause the company financial harm.

But since Kalshi filed its first case last spring, Crypto.com has geofenced Nevada, where a district court judge banned it from operating, and sports betting companies DraftKings and FanDuel, both of which launched prediction markets late last fall, have been geofencing out certain states and tribal land during their rollouts.

“The geofencing argument that Kalshi is maintaining is falling under its own weight,” Wallach said. “Now they’re an $11 billion value company, so complaining about having to spend $10 million or so [per year] on geofencing, that’s a very small percentage of its value as a company. But more importantly, companies like Crypto.com and some of the online sports betting companies are entering prediction markets, and they are geofencing.”

The fact that those companies — as well as Polymarket and Robinhood — are geofencing, Wallach said, ironically supports state and tribal cases because the sports betting companies can do it “at the flip of a switch.”

Better attorneys, more engagement key

Wallach also addressed some key situations that have altered the face of the prediction market litigation. He said that in early lawsuits, states relied on in-house counsel to argue against top-line gaming attorneys, but in many cases have since opted for more expertise via outside counsel.

“[Nevada has] gone from having their in-house attorneys poorly litigating the case to turning over to one of the preeminent Supreme Court shops in the nation and on a dime, the Nevada preliminary injunction which went in favor of Kalshi got dissolved within a matter of months, largely in part because of the involvment of the Tribal Amici, and the engagement of top tier outside counsel.”

He said that as of Labor Day, only three states were involved in litigation with Kalshi, but that number has since risen to 12.