Gambling addict Andrew Douglas had it all planned out.

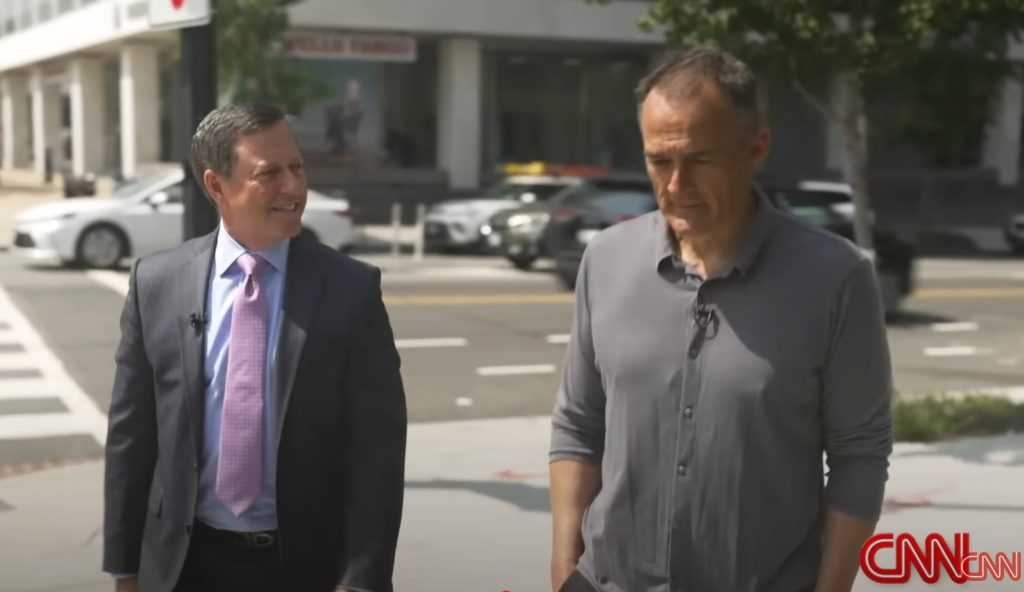

“It just tore me apart from the inside out. I was like, everybody’s going to be better off without me being here,” he told Nick Watt on the CNN special “The Whole Story: Sports Betting: America’s Big Gamble,” which aired Sunday night.

“Being at peace with that decision is the scariest part,” he said. “It was going to be quick and I had everything that I needed to make it happen. But I hear a knock at my door and no one ever knocks on my door because I don’t really have a bunch of friends at this time. I see four officers spread out everywhere in any direction that I could run.”

Douglas, now a recovering addict, was driven to consider suicide at the time over betting. He told Watt, “At first, I was threatening to hurt myself trying to get money. … I sold everything that I possibly could — clothes, TVs. I didn’t look at anything in my house as anything other than a dollar sign.”

It’s the worst-case scenario. But it didn’t happen, and it’s not unique to gambling. While Douglas couldn’t pull himself back from the precipice, his family did. (His concerned father alerted the police.) And with addiction, isn’t it incumbent on the individuals or their family or friends — not the government or offending industry — to get help?

Douglas’ story is terrifying, but it is also uncommon. With it, plus stories of a recovering gambling addict turned addiction counselor and a former NFL employee in prison for stealing $22 million from the Jacksonville Jaguars to gamble, viewers of CNN’s program see only devastation.

What’s the other side of the story?

But that’s not the “whole story” of sports betting and, while CNN may have succeeded in pushing forward an anti-gambling agenda, it did so by telling only one side of the story.

Sunday’s report opens with scenes from Circa Sportsbook in Las Vegas, on what appeared to be the final day of the 2024 NFL season. The sportsbook runs the richest season-long gambling contests in the country and, on the day of filming, Steven Goncalvez is shown as he sweats out the final games to win nearly $2 million in the 2024 Survivor Pool.

Next up is Isaac Rose-Berman, a twentysomething introduced as a “typical sports bettor,” who shows Watt how to place a parlay bet. But after the introduction, we learn that Rose-Berman is anything but “typical.” He’s a pro bettor who analyzes statistics, looks for anomalies in betting lines, and uses his brainpower to earn a living. He also often bets tens of thousands of dollars at a time. Most bettors never do that.

Watt, in his own words, is overwhelmed by the lights and sounds and the suit that Circa owner Derek Stevens is wearing. Stevens is folksy and unassuming but is dressed in a coral-colored sport jacket. (Or maybe it’s peach or salmon.)

Cut away from the cheers and crowds and giant screens to a nearly empty auditorium. Professor Tim Wong, co-director of the UCLA Gambling Studies Program, tells Watt that gambling is “embedded in our DNA.” The next cut is to a sparsley furnished room where Harry Levant, a recovered gambling addict, lobbyist, and addiction therapist, tells Watt, “Gambling addiction is an addiction just like heroin and opioids and tobacco and alcohol and cocaine.”

With the average viewer now likely terrified of sports betting, Watt introduces Bill Miller, president of the American Gaming Association (AGA). Miller has plenty of experience with public speaking, shilling for the gambling industry, and making the argument that gambling is a safe form of entertainment. But within seconds, faced with Levant’s words, he is backed into a corner.

He says he doesn’t think gambling is addictive. After a cameo in which Mark Gottlieb, executive director of the Public Health Advocacy Group, says that “in states where sports gambling, online sports gambling, has been legalized, overall credit scores have gone down and bankruptcy filings have gone up,” Miller says, “That is academia wrapped up in advocacy.”

Watt leaves those words hanging, and Miller looks disingenuous.

Addiction isn’t all that prevalent

The camera cuts back to Rose-Berman, as Watt probes him to see if he can quit gambling whenever he wants. Rose-Berman says he’ll figure out that out when the time comes. The implication — despite the fact that Watt has no proof that Rose-Berman is struggling — is that Rose-Berman is an addict. He later directly asks Rose-Berman if he has a gambling problem

“Depends how you define it,” Rose-Berman replies. “I would say no. There’s like a set of criteria and you have to fulfill five or six out of nine of them. The majority of gamblers get at least a couple of them. The way that gambling affects your brain, it’s very, very difficult to engage with these products in a totally responsible way.”

It’s also unusual to be a gambling addict. Or an addict of any kind, for that matter.

According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, less than 11% of Americans have “substance use disorder.” But we haven’t outlawed tobacco, alcohol, or all drugs. We’ve put guardrails around them, so adults can make informed decisions.

According to the National Council for Problem Gambling, fewer than 4% of Americans struggle with some level of gambling addiction, and only about 1% have what would be considered a full-blown addiction.

Hmm, what about the illegal market?

Further into the report, Watt reads from a graphic that shows $4.8 billion was spent on legal sports betting in 2017, the year before the Supreme Court overturned the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA). At that time, the only place to legally place a sports bet in the U.S. was at a sportsbook in Nevada. The graphic shows how the number ballooned to $147.8 billion in 2024, by which time more than 35 states had legalized some form of sports betting.

What the graphic failed to show is this: In 2017, per the AGA, there was likely $150 billion spent on the illegal market. By 2024, that number had dropped to $84 billion. Those numbers mean that thousands, if not millions, more American bettors are now betting in legal markets, where operators are required to provide responsible gambling tools and clear access to a problem gambling hotline as well as vet players to make sure they are who they say they are — and, in some cases, have money to gamble with. It also means that all of those players will get paid for their winning bets — a guarantee that doesn’t exist on the illegal market.

From here, Fong talks about the betting popularity of Taiwanese table tennis — though Watt calls it Tanzanian table tennis later in the broadcast — due to its availability. Watt follows that by explaining the constant action and betting allows for constant dopamine hits. Therapists who treat all kinds of addictions and disorders know about chasing the dopamine hit. It’s not unique to gamblers. We all chase the opportunity to get that feel-good rush every day, whether it’s by negotiating a good deal, taking a run, going to a party, or successfully building that piece of furniture that came in a box.

Gambling, embezzlement, and suing from prison

But Watt is focused on gambling addicts — not sports betting in America — so viewers next hear Andrew Douglas’ story, and that of Amit Patel, who used a corporate credit card to embezzle $22 million from the Jaguars to gamble.

“Where are you speaking to me from right now?” Watt asks, ominously, with a phone lying on a table. “Exactly where are you?”

Patel: “I am at FTC Montgomery. It’s a minimum security federal prison camp.”

Watt: “You bet like 20 million. How much did you have at the end of all this? Nothing?”

Patel: “Nothing.”

What Watt fails to share until much later is the part where Patel stole the money, though he refers to it as “illegally borrowing” it. And that he spent millions of it on private jets and travel, technology, collectibles, and a private club membership.

Watt does eventually divulge that Patel — who says later in the program, “I will say that not everyone will get addicted, but anyone can get addicted” — is suing FanDuel for $250 million from prison.

Miller says it like it is

Of those who spoke meaningfully in Watt’s expose, 14 were opposed to all forms of gambling, recovering addicts, or anti-legal gambling. Six were in some way involved in the industry and, of those, only one — the AGA’s Miller — was given a chance to argue the merits of legal gambling.

Miller told Watt that the gambling industry has a responsibility to keep gamblers safe, to offer tools to keep gambling in check. Miller said the legal industry itself has flagged the biggest gambling scandals, which he referred to as “anomalous behavior,” since PAPSA was overturned.

We left Miller all but accusing academia of being less than a neutral observer. There are plenty of examples — studies funded by pro- or anti-gambling groups that appear to be unbiased research. Miller is just the first one to call them out in public.

Later in the report, Miller tells Watt, “People that are irresponsible and that are anti-gambling, they would like to lump it all into some dynamic that is similar to the tobacco companies. I find that absolutely abhorrent and offensive. An industry that nine out of 10 Americans believe is an appropriate entertainment form is being compared to something that kills people. That’s not appropriate.”

The first part of that clip is one that CNN used to promote the report. Out of context, it feels ugly. But in context, Miller is right. Comparing gambling to tobacco, alcohol, or drug addiction is abhorrent. Science tells us that the second we inhale, drink, swallow, or inject, we damage our lungs, livers, hearts, and other vital organs. The first time we gamble? We get a dopamine rush. From there, most people don’t ever suffer physical “damage.” But as we know, for a small percentage of people that dopamine hit is the start of an addiction.

Those on that journey face a difficult and scary road that often leads to other addictions — or co-morbidities, as the medical community refers to them. It can be hard to untangle if a gambling addict started as an alcoholic or if a drug addict started as a tobacco user. Or, if any addict has another factor — an attention deficit disorder, depression, or PTSD — that opened the gateway to addiction.

But CNN didn’t share the “whole story.” It shared the agenda Watt wanted to push forward.

He closed with this: “The game has changed. Now we as a society have to decide how much we’re willing to gamble. And the stakes are as high as the thrills.”

Except they’re not.