When Sam Favata put his first dollar in a slot machine in 1980 and won $3, he thought, “This is easy.” So he took his winnings and the $200 his dad had given him for incidentals for the weekend and headed to the craps table. He bought in for $20 … and lost. So he bought in for another $20 and, soon after, his $200 had grown to $300.

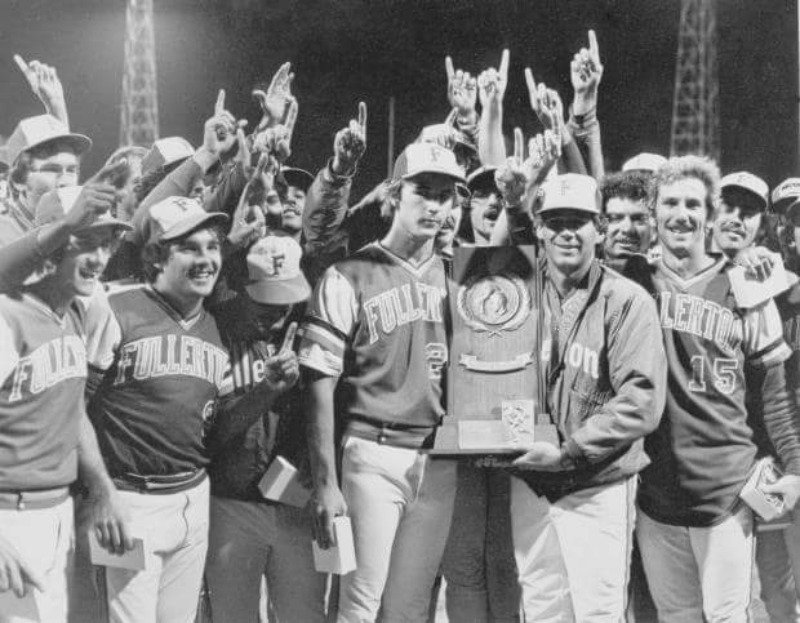

The action was exciting and fast. As he stood at the table with 10 teammates from the defending College World Series champion Cal State Fullerton Titans, drinking a diet cherry soda, it was a heady couple of hours for the 19-year-old. When the night was over, Favata had “like $3 left for a Coke.”

And he had a phone call to make. “I called my dad and said, ‘I lost everything,'” he recalled. “And he was like, ‘What?’ Boy, was he disappointed. But he said, ‘Don’t worry about it. I’ll be there tomorrow, I’ll give you another $100, just promise me you won’t gamble.'”

Favata made that promise, but then took $25 of that new $100 and played a slot machine. “I was, like, hiding in a corner doing that, so my dad wouldn’t see me,” he said.

It was only the beginning.

The previous June, Favata scored the winning run when Fullerton won the first CWS in school history. It was another incredible moment in a baseball career already filled with incredible moments.

Favata, a blue-chip recruit out of Edgewood High School in West Covina, California, had been drafted in 1977 by the Los Angeles Dodgers in the 18th round. He opted instead for college, which he hoped would lead to a career in the major leagues. He chose Fullerton over offers from baseball powerhouses like Arizona State and Southern Cal, which by Favata’s freshman year (1977-78) at Fullerton had won a combined 15 CWS, including a record five consecutive by USC between 1970-74.

He was a handy and speedy second baseman who batted .350 or better and had a gift for stealing bases. During the 1979 college season, Favata hit a then-record .418, led the nation in hits (116), and was second in stolen bases (66). His national batting average record stood for 16 years before current Athletics manager Mark Kotsay broke it. Favata was a two-time All-American who was taken again in the MLB draft, this time after his junior season in the 13th round by the Milwaukee Brewers.

Gambling losses trumped game losses

The 1980 season at Fullerton didn’t start the way Favata thought it would. An early February series against UNLV was his first visit to Las Vegas, though not his first brush with gambling. It also marked the first time that Favata recognized he might have a gambling problem that ultimately would bleed into the rest of his life.

He said he didn’t have a “good showing” in the series, and on the drive home, “I was more upset about the gambling losses than the game losses.”

“I got two hits in the first game, but we lost, and then I went 1 for 10. It was horrible,” he said. “My mind was was like 70 percent gambling and 30 percent baseball. I saw the lights, the sounds, and I was, like, I gotta come back.”

Boy, did Favata go back. When he eventually accepted a plea deal from federal authorities on charges of fraud on April 20, 2006, he had a million-dollar marker at the Rio, which he could call on a moment’s notice and set up a luxury getaway complete with private elevator, 3,000 square-foot suite with a pool, all the liquor and champagne he could drink, and all the chocolate strawberries he could eat. (He was also a VIP at Caesars from 1987 to 1996.)

That was just in his suite. Throughout the hotel, he used a card that covered everything from restaurants to coffee and alcohol. “I mean, when you’re playing $1 million in a weekend, then 50 grand on food … what’s the big deal?”

But Favata’s real addiction was sports betting, though he is adamant that he never bet on baseball when he was a player.

Before the advent of the internet, Favata placed bets with — and collected hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash in pizza boxes from — infamous bookie Ron Sacco. By the time technology made meeting the corner bookie obsolete, Favata was betting offshore with Sacco as his point of contact.

“If I didn’t have that itch for gambling or that greed or compulsion or whatever you want to call it, if I hadn’t got that taste for gambling, I don’t think I would have ever gone to prison,” Favata said. “It’s what caused problems with my relationships, baseball world, everything.”

In the end, gambling landed him at Lompoc (California) federal prison for 33 months. It cost him nearly three years during his daughter’s formative years, as well as the trust of friends, his career, and his reputation.

Tragedy and recovery

Favata, 66, says he was lucky. His wife Sandra visited him with their daughter Kindy every weekend at Lompoc. His parents stood by him. He lost some friends — or people he thought were friends — but many supported him then and still support him now.

That three-game series in Las Vegas in 1980 was indicative of what Favata’s life would become. He was, for lack of a better term, a functioning gambler. He said friends and family knew he gambled, but didn’t have any idea how much or how often. And for many years, he didn’t bet more than he could afford.

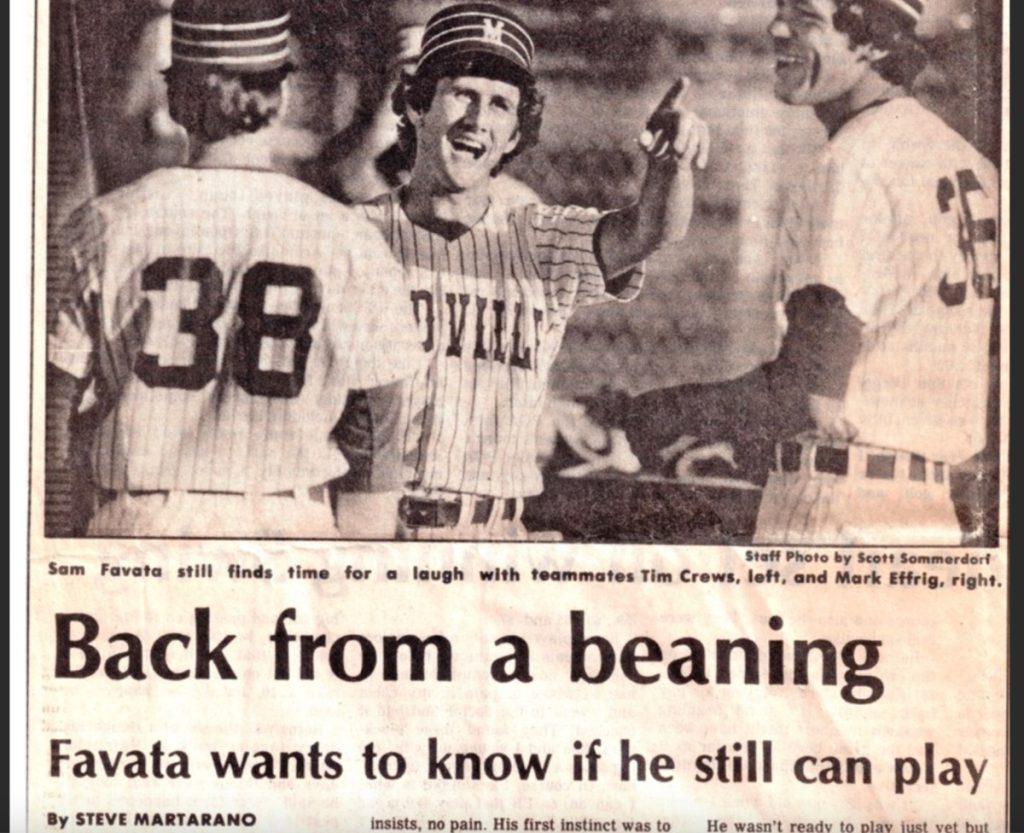

The beginning of the end of his baseball career was a summer night in Modesto, California, in 1981 during which he was beaned with an 87 mph fastball that dropped him at home plate. The pitch almost laid him out for good. Favata didn’t know it at the time, but the doctors at the trauma center in Modesto weren’t sure he would live — never mind walk, talk, or play baseball.

Favata needed surgery to drain three brain bleeds, but once the worst of it was over, he applied his athlete’s focus, concentration, and desire to overachieve at physical and occupational therapy. He regained his speech and ability to walk and nine months later was begging the Brewers to take him back. They eventually did, and Favata’s comeback took place at the same field on which he was beaned. According to the Sacramento Union, when Favata ripped a single to right field, the crowd of 4,989 gave him a three-minute standing ovation.

“Although I had a hard time talking, writing, and moving around, my mind was always clear,” Favata told the Union. “I never really thought of not coming back, of not playing again. Everything happened so fast — getting hit and then recovering. Once I realized I was improving, I was determined to play again [that] season.”

Everything about Favata’s recovery was remarkable. His physicians expected him to be hospitalized for up to six months, but he walked out of the Doctors Hospital in Modesto 10 days after the beaning. Playing baseball seemed out of the question to everyone but Favata. On one hand, he was realistic. But after that first game, Favata knew he was back on the field because he wanted to be, and he would decide what his future would be.

“I just want a fair shot at winning my old job back,” he told the Union. “I have a lot of other things to consider. And if I’m not the same ballplayer I was before, I want to find that out and not be kept around just because I’m the guy who came back from the beaning.”

Favata never really got the chance. Before rejoining the Brewers’ High-A farm team, the Stockton Ports, he had to sign waivers of liability, and he wasn’t used as an everyday second baseman. Instead, the Ports slotted him in as a pinch runner and sometimes as an outfielder. A second hit to his temple would have been devastating, and the team didn’t want to take that chance, even if Favata, for a moment in time, thought he did.

Playing the ponies a favorite

A few months into his comeback, Favata decided to hang up his cleats. He took a job as a scout for the Brewers in 1983, and though gambling had taken a backseat to his recovery and comeback, his addiction soon came back with a vengeance.

He was 22 years old, living with his mom, and still collecting workers’ comp in early 1983 after the hit to his head. But with the scouting job on the horizon — he was offered the gig in November 1982 and had to report to what would be his home base in Santa Clara in March — he took one of his $400 workers’ comp checks and, in January, went to the Santa Anita racetrack, where he kept doubling down on horses to “show,” turning $400 into $6,000. He took his winnings and bought a new car, and his betting began to escalate.

Gambling was part of Favata’s life from his childhood, which started in Tampa. His second cousin was notorious and powerful crime boss Santo Trafficante, Jr., who oversaw mob activities in Florida and Cuba while maintaining close ties with New York’s Bonanno crime family and the Chicago Outfit, headed up by Salvatore Giancana. Favata’s father, Joe, ran numbers for Trafficante and introduced Sam to the racetrack, but fled the life before becoming a “made man” to give his son what he hoped would be a better life in California.

Sam was a youngster when his family left Florida for California. He’d already been introduced to gambling, and his father took him to the racetrack in Los Angeles, though he warned a young Sam off gambling. To this day, Favata says he thinks a penchant for gambling is in his DNA.

Bears win, and so did Favata

Favata doesn’t make any excuses. Though gambling was a part of the fabric of his world, he owns his mistakes and he’s first one to tell you that there were many. The gambling itself wasn’t the worst part. When he was winning big, he had a ball. When he was losing big, he once had to sell a condo to cover his debts. Either way, he was lying to everyone around him and living a double life.

But when he served as a partner in a mortgage company and started using other people’s money to cover his debts, he began to understand something was terribly wrong.

After leaving scouting, Favata in 1982 began a professional odyssey of coaching at a new business started by decorated Fullerton baseball coach Augie Garrido, and then at his alma mater, Edgewood High School, before moving into the title business after a former teammate told him he could make a six-figure salary. He eventually went into the mortgage business, first with a friend, then opened National Consumer Mortgage (NCM) in 2000.

Meanwhile, Favata renewed his commitment to church and met his wife. They had two children, one a son who died a year after being born. He also got a $450,000 settlement related to the beaning, allowing him to buy a buy a condo and a new BMW. Behind the job moves and personal tragedy, Favata’s gambling escalated. He went from betting a few hundred dollars on a game to thousands, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, and in a handful of cases, a million-plus.

In 1986, Favata made his biggest bet to date — $165,000 on the Chicago Bears, giving 10 points against the New England Patriots in Super Bowl XX. The Bears won big, 46-10.

Bet looked better after speaking at church

Later that year, Favata was asked to give a motivational speech at a church. He talked for an hour as, all the while, a bet was swimming around in his mind. When the talk was over, Favata asked the pastor if he could make a phone call.

“I’m thinking, ‘This is a sure thing. I just spoke here, I’m at the church, I’m going to bet the Angels,'” he said about calling Sacco to bet $80,000 to win $50,000 on a California Angels-Cleveland Indians game. “I liked the matchup. It was a lot of money for a regular-season game, but I just liked it, and I liked it better after I spoke at a church for an hour. Because I’m in church, God’s going to bless me.”

Favata won that game. “I’m on fire,” he remembered thinking. “I’d win seven games and lose two. Or win nine and lose one. It’s irrational thinking, you know. It’s not right, that kind of super positiveness. You don’t think you’re going to crash someday.”

The hot streak lasted several years, but eventually he started losing more than winning. Still, he kept betting. By the late 1990s, he had to take time off from the mortgage business to care for his sick son, Joey, and had to sell his condo to pay gambling debts.

In 2000, he founded NCM, a company that the Los Angeles Times called a Ponzi scheme. Favata convinced clients to refinance their homes and use the proceeds to “invest in another arm of the company promising investment returns of 30%-60%” annually. But there were few other investments. For the most part, Favata was using money from new customers to pay older ones and to finance his own living expenses, including gambling. By the time he turned himself in, he owed clients $32 million.

The scheme lasted six years, with NCM doing as much as $400,000 in monthly revenue and Favata regularly betting large amounts on games. His biggest single bet ever was $1.425 million on a regular-season Boston Bruins-Ottawa Senators NHL game in 2005. He had the Senators at -400 with a chance to win $400,000. He used cash to place the bet at the Rio. The Senators lost. Favata took money from NCM to chase his loss.

By 2005, Favata had an offshore account with Costa Rica-based 5 Dimes. That year, he scored one of the biggest wins of his gambling career — a $985,000 payout on a $45,000 six-team March Madness parlay. He also hedged the final game and managed to win both the parlay and the hedge bet, increasing his overall winnings on the game by several hundred thousand dollars.

SEC opens investigation

In 2006, Favata learned that the Securities Exchange Commission was investigating him when an agent contacted his wife and he began to hear from investors that investigators were calling. He decided to turn himself in before an arrest warrant was issued. Among those who spoke to his character was longtime friend Steve Garvey, a 10-time MLB all-star over a nearly 20-year baseball career, mostly with the Dodgers. Garvey had shilled for NCM, but was unaware of Favata’s actions.

Represented by current Los Angeles County District Attorney Nathan Hochman, Favata was charged with one count of mail fraud, which carried a maximum sentence of 30 years. With an elementary-school-aged daughter at home, Favata was terrified that he’d miss her childhood. He was sure there was a way out until he says Hochman told him, “The only way you’re not going to prison is if you find Bin Laden.”

In the end, Favata served 33 months at Lompoc and six months in a halfway house. He considers the relatively short sentence a gift. When it was over, his wife and daughter welcomed him home. He attended Gamblers Anonymous meetings, tried to stay away from the temptation, and worked to find his footing. But he stumbled and landed back in prison for 100 days after violating his probation by lying about a job situation. His probation was extended by just over two years, including six more months with an ankle bracelet.

From the day Favata learned of the SEC investigation until the day he was released from probation was nearly 10 years. U.S. District Court Judge Andrew Guilford ordered Favata to pay restitution of $10,000 per month to his victims, some of whom lost as much as $3 million. At that rate, it would take 266½ years to pay back the debt. But Favata says he’s paid back about half of the $32 million he owed via an NCM bond that came due and after testifying in a case against the Rio that sent $2 million to investors.

Favata paid the $10,000 per month before he entered Lompoc, at which point he was wiped out financially and had no assets. Since his release on Sept. 7, 2010, 25% of his earnings, including Social Security, have been garnished. He doesn’t own a home or have credit cards. And he is no longer living large.

At Lompoc, Favata participated in the Residential Drug Abuse Program, an intensive daily course in which addicts address responsibility, accountability, and the “damage” their addictions have done to others. He says he understands that the people he swindled “will never trust financial advisers again.”

Favata’s dad — long his biggest cheerleader — died while Favata was in prison. He couldn’t be with his father or attend his funeral.

“My counselor asked me the next day, ‘How do you feel that you weren’t there for you dad?’ and I wanted to punch the guy, but I take full responsibility, and if it weren’t for my bad choices, I would have been there for my dad,” Favata said of the pain he still carries because of that absence. “But he was proud of me and he’d told me, ‘You’ve had a great first seven innings, a rough eighth, now finish strong.”

‘I was the perfect guy … what the hell happened?’

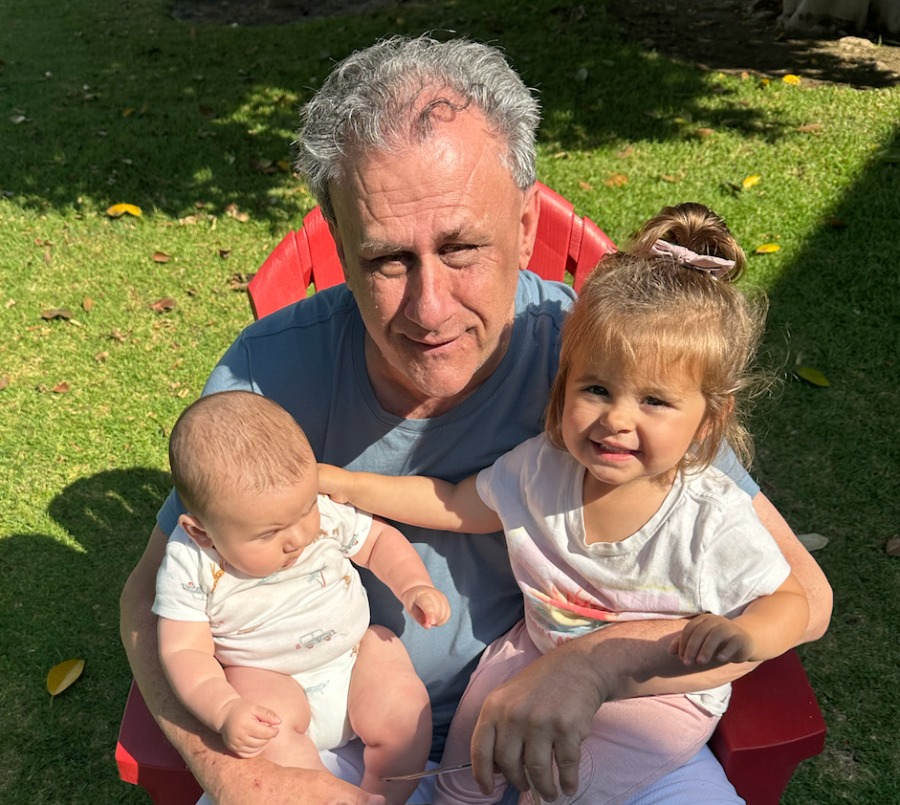

Today, Favata is a doting grandfather, a public speaker, and a man of deep faith. He hasn’t been to Gamblers Anonymous in some time, but his addiction is always lurking. He keeps it at bay by focusing on the good in his life — his wife, his daughter, his “grandbabies,” and how he doesn’t want to lose those relationships.

“I was the perfect guy growing up. I was an athlete, I went to college, I was honest, but what the hell happened to me?” Favata said. “It was an addiction. I was an athlete, a coach, and all the secrets inside of me … it sucks.”

Sitting in a Southern California diner near his Orange County home detailing his ordeal, Favata is affable and optimistic. He’s also contrite and ready to share his story, so that maybe, somehow, some way, someone will learn from his mistakes.

“It helps me to get it out,” he said. “It’s like therapy to me to help people who are going through it. There are a lot of people who are going through worse than what I went through and are going down the wrong road. I thought I was a humble person, I always wanted to treat people fair and nice and be respectful, and it’s the biggest thing in the world to be humble.

“I’m very sorry, I’m very humble. I know I messed up. I was at the top of the mountain as a baseball player and then down to the lowest possible point. Before I leave this world, I just want to help people.”