Kalshi’s decision to self-certify a contract on the NCAA transfer portal generated a major reaction, even though it now seems it may never actually take bets on the topic.

Amid the backlash, Kalshi announced it had “no immediate plans” to let people bet on who enters the portal, and noted that not every contract that is self-certified goes up on its site.

But the controversy may raise questions about both Kalshi’s listing procedures and how rules about trading on insider knowledge work in CFTC-regulated prediction markets.

Why did Kalshi self-certify portal market?

It’s not immediately clear what steps led to the contract being self-certified, particularly if there really were no immediate plans to actually offer the contract to customers.

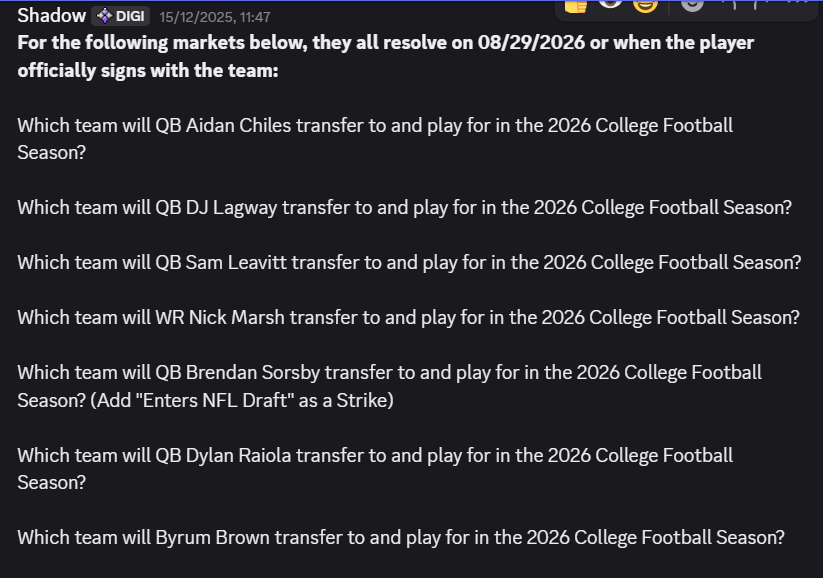

Kalshi takes suggestions for markets from its users via Discord, its social media channels, and a form on its website. It doesn’t self-certify every market, but the transfer portal filing raises questions about the steps involved when Kalshi decides to put up a new contract.

Just a day before the self-certification document was filed, a user on Kalshi’s “market suggestions” Discord channel suggested a series of bets on whether certain players would enter the transfer portal, as well as the next destination for players who have already signaled intent to transfer.

That user said they would market make — put up prices on both sides — for these markets, and added that they were “being told so many things.”

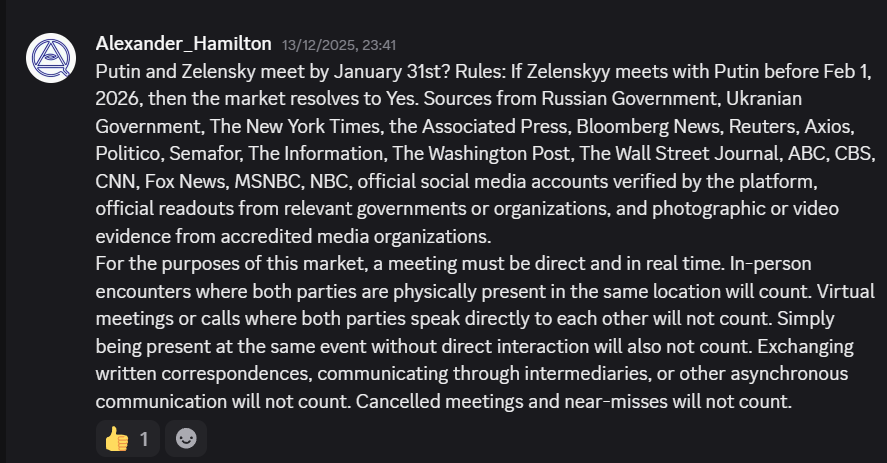

Other contracts recently suggested in Kalshi’s “market suggestions” Discord channel have been self-certified soon afterward. For example, this week Kalshi also self-certified a contract on whether “<person 1> will meet <person 2>,” just two days after a user suggested a contract on whether Vladimir Putin would meet Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

A Kalshi spokesperson did not respond to InGame’s request for comment on whether the transfer portal self-certification originated with an idea from the Discord channel, or the steps taken between user suggestion and self-certification of a market.

Kalshi’s website says: “We analyze all markets that are suggested to make sure that they are compliant with CFTC regulations, not easy to manipulate, and are in the interest of our users, so we cannot promise that every market suggested will make it to the platform.”

A separate page on the Kalshi website says: “Before a new market is approved for trading, it undergoes a thorough review by the Kalshi team and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). The review ensures the market meets regulatory requirements.”

But details on what this entails are not always clear.

Kalshi’s markets department takes the lead on determining which contracts to self-certify and drafting rules for them. Kalshi’s Head of Markets Xavier Sottile sends all self-certification filings to the CFTC.

CFTC insider rules differ from SEC

The backlash to the contract also highlights a detail in how insider trading rules actually works.

Many critics raised questions about the fact that a large number of people could have insider information about a college athlete’s decision to enter the transfer portal, or their next destination.

Many potential insider trading scenarios would have at least been prohibited by Kalshi’s house rules.

Like with all markets, Kalshi took steps to limit insider trading with its list of people who are not allowed to trade on a specific market. In the case of the transfer portal market, that would include the athlete, their family, and their teammates, among others.

In its response to the backlash, Kalshi’s news team addressed this directly, noting that “users with material nonpublic information would be prohibited from trading on potential transfer portal markets.”

But in doing so, Kalshi actually goes above and beyond what the CFTC would have required.

However, that means the CFTC may not have been closely scrutinizing whether those prohibitions would have prevented insider trading, because the CFTC only bans trading based on material non-public information in specific circumstances.

In markets regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), trading based on material non-public information is generally not permitted.

The same applies for regulated sportsbooks in many states, and even in states where the rules are somewhat less clear, athletes, coaches, league officials and other similar roles are usually explicitly banned from using inside information to bet.

On the other hand, CFTC insider trading rules are deliberately narrow. The commodity futures market was originally created in order to allow market participants such as farmers to hedge based partly on their own knowledge and activity of their business. That means market participants trading based on their own actions is the entire purpose of the futures market, which has since evolved into the wider CFTC-regulated infrastructure.

As a result, the Commodities Exchange Act still does not have general bans on insider trading, but instead focuses on the standard of “misappropriation” — whether the knowledge being traded on was obtained illegally, dishonestly, or otherwise with the expectation that it was not to be shared. Bans on fraud and manipulation also prevent insiders from manipulating the outcome of the actual underlying event of a contract in order to profit from the contract, in a manner similar to match-fixing, or knowingly presenting misleading information about their actions.

Eddie Murphy v. NCAA

The ban on misappropriated information, introduced in 2010, is sometimes nicknamed the “Eddie Murphy rule,” because of the scheme at the climax of his 1983 film Trading Places, in which commodity traders attempt to use a stolen orange crop report to make money off of the orange juice futures market. When the film was released, the plan did not actually violate CFTC rules.

And misappropriation covers many possible insider betting situations. A coach passing on confidential information about a player’s injury status to a gambler could be misappropriation. But subjects such as a college athlete’s transfer plans involves less formal confidentiality and therefore information may be able to be passed on without misappropriation.

While today, use of misappropriated information to trade is clearly illegal, the CFTC still has no prohibition on trading with insider information that is obtained legally and honestly, provided there is also no attempt to manipulate the market.

That means that the onus for enforcing bans on honestly obtained insider information and manipulation-free insider information may mostly be on Kalshi: they are house rules rather than CFTC requirements.

Kalshi for its part appears to have some serious measures in place to monitor potential trading prohibition violations: it is partnered with sports betting compliance business IC360 to monitor activity for potential integrity violations.

CFTC still has some enforcement power

That’s not to say that it’s a matter outside the CFTC’s jurisdiction altogether. The regulator’s Core Principle 2 concerns exchanges actually enforcing their own house rules. If an exchange fails to enforce its rules, the CFTC can take action.

The CFTC typically performs rule reviews of DCMs, to ensure that they are enforcing their own rules, though the frequency of these reviews can vary.

In that sense, the CFTC still plays a part in the enforcement of insider trading prohibitions. However, that role is indirect, and comes alongside efforts to ensure hundreds of other house rules are enforced correctly. With the CFTC short staffed, it may be a difficult ask for it to ensure a prediction market fully enforces its own trading prohibition rules.

And while Core Principle 2 means that the CFTC can take action against an exchange for not fully enforcing its own rules, it has less power when it comes to the people who might trade on inside knowledge. Those insider bettors may get banned from Kalshi, but — provided they haven’t broken the CFTC’s own rules — could escape action from the CFTC or federal government.

In contrast, an insider who bets on insider information for a sportsbook or at an SEC-regulated financial exchange — or those who pass on that information, if they know it will be used for gambling purposes — could still be charged with a crime. That arguably leads to a very different risk/reward scenario for the prospective insider bettor.

Is insider trading beneficial?

Some have argued that the use of insider information in prediction markets is a feature, not a bug, as it allows for information to become widely known more quickly. Last month, Coinbase CEO Brian Armstrong said he had a “really interesting conversation with one of the folks who was nominated to be CFTC commissioner” in which he argued that “you actually want insider trading” in many circumstances, in order to provide a signal to people looking for information, but that this has to be weighed against integrity concerns.

The fact that CFTC rules themselves only prohibit certain types of insider trading also opens up an additional scenario. An exchange could decide that having to enforce rules beyond what its regulator asks isn’t worth it, and limit its bans on insider trading to those who have obtained their edge illegally or dishonestly. Polymarket’s non-U.S. site, which is not subject to CFTC jurisdiction, has no specific ban on insider trading — even if the information is misappropriated — though its U.S. rulebook clearly prohibits all insider betting activity on that version of its exchange.

Other exchanges active currently appear to have similar prohibitions.

Right now, that scenario appears to be hypothetical, but as more prediction markets enter the space, could it become real?