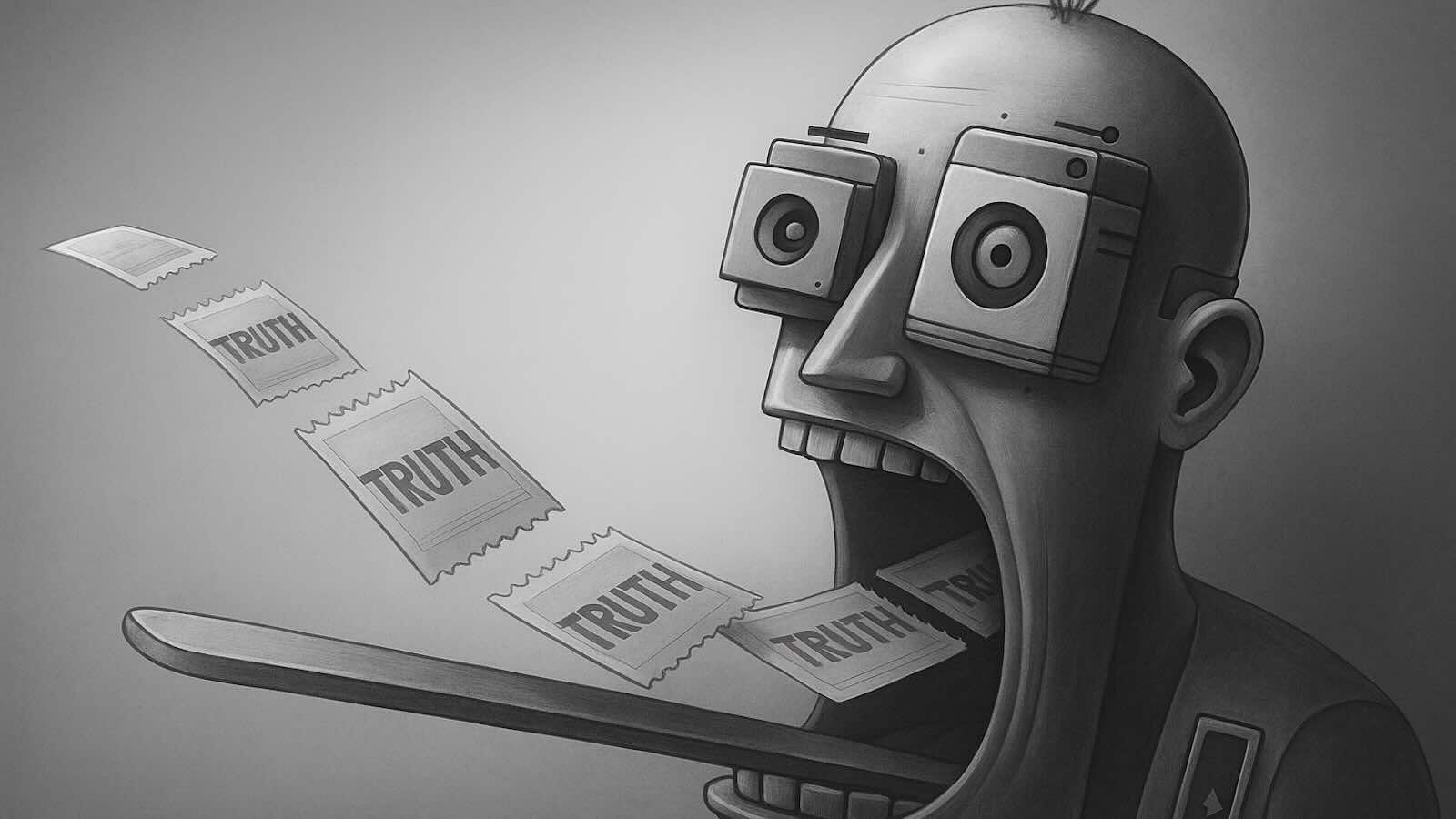

Tarek Mansour, the CEO and co-founder of Kalshi, turned heads twice this spring with his use of the word “truth” on the social media site X.

On March 30, as his company — the boldest prediction-market operator in terms of branching out aggressively into legally gray territory — began taking its right to offer sports event contracts to the courts, Mansour wrote, in defense of prediction markets:

“They are the quintessential truth machines.”

And on May 20, in a since-deleted post temporarily announcing the supposed (but ultimately inaccurate) news that Kalshi had partnered with xAI, Mansour delivered these words:

“No one has fought for truth harder than Elon Musk.”

To those working in the regulated gambling industry and/or to those on a particular side of the political fence, either of Mansour’s applications of the word “truth” had the potential to cause eye-rolling of the highest order.

How hard the richest person in the world fights for truth is a debate best suited for other websites.

But whether Kalshi and other proprietors of prediction markets provide humanity with “quintessential truth”? That’s a topic directly aligned with InGame’s areas of expertise.

And it is, to a great extent, a matter of semantics. What does “truth” mean to you? We’re not asking in the “alternative facts” sense, where certain folks may tell you not to believe the evidence seen with your eyes or heard with your ears. Rather, in a hypothetical world in which we can all get back to believing the same basic facts, does truth have to be a conclusive endpoint? Or can truth apply to the closest possible reflection of reality at any point along the journey to that endpoint?

“Prediction markets show a likelihood, not a sure thing, and I think a lot of people really want binary answers,” said John Holden, an associate professor at Indiana University’s Kelley School of Business, whose research focuses in part on gambling. “They want to know, ‘Yes, this is going happen.’ And that’s not what these markets do.

“A lot of the knocks on the mechanics behind prediction markets largely come from a misunderstanding about what they’re showing and when they show it. You know they’ll show the correct result at the end, which is what you want, but it doesn’t always give you weeks and months of a heads-up as to what’s going to happen.”

The truth is out there

Part of what Holden said is obvious, but it’s worth repeating: Eventually, prediction markets will always tell the truth — just as tomorrow’s newspaper will always have the correct score of the ballgame.

In an extreme real-life example, with exchange wagering on the 2020 U.S. presidential election, markets were not settled on election night, or the next day — or in some cases, even the following weekend when the major media outlets all confirmed Joe Biden had beaten Donald Trump. Election denial was in full force through that November, that December, and through Jan. 6, 2021, and there were still people taking and giving action on Trump until Biden was sworn in on Jan. 20.

At a certain point, though, markets resolve and the truth cannot be (reasonably) debated.

The question at the heart of Mansour’s “quintessential truth machines” argument is whether prediction markets foretell that eventual truth with more accuracy than other methods.

In the case of elections, yes. In recent cycles, odds and prices on sites like PredictIt, Betfair, Polymarket, and Kalshi have generally proven more accurate than most polling. For example, last October, a little over a week before Trump defeated Kamala Harris to regain the presidency, a national aggregation of polls had the candidates virtually tied, but Polymarket pegged Trump as a 61.7% favorite. The “truth machines” case was solid.

On the flip side, odds at Kalshi and elsewhere were way off base last month, when Robert Prevost was barely on the radar before being named the new pope. Those markets gave no indication of the “truth” until everybody already knew the truth.

What was Mansour’s response?

He made no mention of “truth machines” as he celebrated how “beautiful” it is that you can make big money when the prediction markets attach a low probability to what turns out to be a winning wager. (In other words, when they’re not a source of “truth” at all until the very last stage of the process.)

Statistician and media personality Nate Silver — who it must be pointed out serves as an adviser to Polymarket, a prediction market operator not available to U.S. customers and the one that ultimately ended up securing a partnership with Musk’s X — offered analysis of why prediction markets failed on pope betting as compared to election betting in a recent blog post.

“The single situation where prediction markets have routinely most impressed me is on election days when votes have begun to be counted and markets are trying to forecast the winners based on incomplete information,” Silver wrote. “They are frequently much faster to hone on the correct winners than the mainstream media, which can be reluctant to ‘call’ winners and risk having egg on their faces later.”

Silver continued, after listing reasons why prediction markets tend to be accurate for elections: “In contrast, for a papal election, pretty much the opposite is true on every indicator. The choice of the pope presumably doesn’t have broader implications for financial markets, so well-capitalized institutional investors are unlikely to be involved. The modal trader probably knows little about the Catholic Church. Papal elections occur extremely rarely. And papal conclaves include relatively few participants, and they’re sequestered to prevent any leaks to the outside world.

“In such situations, the conventional wisdom can just feed back on itself.”

Translation: Sometimes prediction markets are reliable sources of truth, and sometimes they aren’t at all.

And someone like Silver is inclined to analyze why they may fail, whereas someone like Mansour is inclined to just declare it “beautiful” when they fail.

The aggregation of information

“I understand what [Mansour] is going for and where he’s coming from, but at the same time, it’s a bit over the top,” said Harry Crane, a statistics professor at Rutgers University and a researcher of and longtime participant in various forms of gambling.

“I’m not sure I get the ‘truth’ aspect of it. I don’t think it is about truth. It’s a way of aggregating information across a large number of people, and it does so anonymously more or less, and the fact that I can participate anonymously without anyone knowing I participated, without anyone knowing why I did what I did, that is an incentive that is a protection against any concerns I may have about letting people know what I know. And, obviously, the incentives of participation are that if I do it right and if my information is accurate, then I would make money on it.

“So I think that’s what these markets are good for. That’s what they do — they aggregate information. And I guess you can make an argument they’re the best at doing that.”

Certainly, prediction markets and betting exchanges have proven better at that than polls over the past decade or so, which Crane finds wholly unsurprising.

“First off, a market is an answer to a different question than a poll is,” Crane said. “A poll is asking people who they want to win. A prediction market is asking people who they think is actually going to win.

“And markets have a significant information edge. A poll is one piece of information, and a market is incorporating information from as many sources as possible, which includes polls. So if the markets are incorporating polls plus, then they should be better. Or they should be at least as good, because if the polls truly were the source of truth, then the markets, if the markets are good at anything, they would just use the polls, ignore everything else, and they would be exactly the same.”

Dartmouth Professor of Economics Eric Zitzewitz, an expert in prediction markets, believes one edge prediction markets have over polls is that the former involves people putting their money on the line, greatly increasingly the chance that they truly believe in the market in which they’re investing.

That was a line of thinking endorsed in April by New Jersey gubernatorial candidate Steven Fulop, in response to a Twitter/X post showing his price rising at Kalshi:

Zitzewitz also noted that “polling has gotten really hard,” both because of unreliable response rates and, as it pertains to presidential elections, the “shy Trump voter” remains a real phenomenon. While Zitzewitz doesn’t believe anyone should draw conclusions about prediction market efficiency from any single election cycle, he pointed out that not only were the markets more accurate than the polls in 2016 and 2024 when Trump won, but they also did a slightly better job than the polls in 2020 of foreseeing a sweat-it-out win for Biden.

All in all, Zitzewitz is a big believer in prediction markets, even if he tiptoes around endorsing Mansour’s “truth” proclamations.

“I have studied the efficiency of prediction markets, and they are really well calibrated,” Zitzewitz said. “If you have no other way of ascertaining the probability of an event and you have a prediction market that’s trading at 80 cents, 80 percent is a really good estimate of the probability of that event. I find prediction markets highly useful as an objective way of measuring the probability of economically important events.

“There are some small inefficiencies in prediction market prices. There’s consistent evidence of what’s called a favorite-longshot bias, where the longshots are a bit overpriced relative to the favorites. If something’s trading at 10 percent, it may only happen 7 or 8 percent of the time, and it’s important to know about that bias when you’re interpreting the chance of fairly low-probability events. But, with little caveats like that aside, I think they’re really quite useful and efficient.”

Crowds and wisdom

Again, there’s a semantic argument to be had about whether “truth” can be applied to a situation in which what you’re really saying is, “This system is probably a more accurate guide than other systems.”

InGame reached out to Kalshi for further explanation from Mansour of his “quintessential truth machines” claim and, though the CEO did not offer a comment, a spokesperson for the company did.

“Prediction markets have a long history of outperforming other methods of prediction (like polling or expert analysis) across a wide range of topics, such as predicting the winners of elections or forecasting Federal Reserve decisions,” the Kalshi spokesperson wrote in an email. “This is because prediction markets combine two very powerful forces: the wisdom of the crowds, and skin in the game.

“Essentially, prediction markets are ‘truth machines’ in the sense that they create probabilities on real world events that are devoid of narrative or bias typically found in polling or media.”

For his part, Holden doesn’t push back on the company line or on Mansour’s “truth machines” wording.

“I’m a big proponent of legalizing prediction markets,” Holden noted. “I think they have a usefulness beyond academic or esoteric utility. We talk about this idea of the ‘wisdom of the crowd,’ and it’s scientifically shown that it’s better than a lot of the other systems that we have. So, from that perspective, I think [what Mansour is saying is] correct.”

Of course, as shown with the pope markets and the various forms of spin/analysis there from Mansour and Silver, when dealing with percentages and probabilities, there’s always an out, a way to claim the markets weren’t “wrong.”

Famously, a little over a week before the 2016 presidential election, Silver’s website at the time, FiveThirtyEight, projected an 85% chance that Hillary Clinton would defeat Trump. When Trump prevailed by capturing several critical “Rust Belt” swing states to win the electoral college, Silver and his backers were able to say, in effect, “We didn’t get it wrong. We told you there was a 15 percent chance this would happen.”

We talk about this idea of the ‘wisdom of the crowd,’ and it’s scientifically shown that it’s better than a lot of the other systems that we have.

— John Holden

Holden again isolates the way “truth” can be a moving target.

“This is all sort of this temporal issue,” he said. “Certainly when that last out is recorded, those markets are going to reflect the winner. A lot of people will say, ‘It was wrong’ or ‘It changed,’ and yes, these shifts do happen, and sometimes they happen quite late.

“So I might put an asterisk on what [Mansour is] saying. In some ways, I think it’s a bit of an oversimplification. Eventually, prediction markets detail the truth. It may not be at the moment that you’re looking at it. But by the time the game ends, the election’s over, they’ll be accurate.”

Fact, fiction, prediction

Before that end point is reached, as Crane points out, there can be different levels of possible certainty depending on what type of market it is. But he also said even the extremes of that spectrum aren’t as far apart as they may appear.

At one end of that spectrum would be a market on whether a specific individual will perform a specific task that they have already made up their mind to either do or not do. At the other end is the result of a sporting event where anything is possible before the game starts, where the random bounce of a ball can separate winners from losers.

“If you’re asking, say, ‘Will Elizabeth Warren vote to confirm RFK Jr.?’ in that instance, before Elizabeth Warren goes to vote, she knows what she’s going to vote for,” Crane said. “So, in a sense, there is a notion of truth. Whereas, before a game plays out, anybody could win, more or less.

“But what I would say is, the way I view it, if I don’t actually know how Elizabeth Warren is going to vote, I’m just doing my best at guessing, right? And it’s the same thing with the sporting event. I’m just doing my best at guessing. I would come up with a price, and I’d say, ‘I’m pretty sure she’s going to vote this way,’ and maybe I’ll pay up to 85 cents for it. And the process would basically be the same with the sporting event.”

Sports outcome contracts at prediction markets are a relatively new entry on the U.S. scene — though sports betting exchanges are effectively the same thing and have a more established track record, dating to Prophet Exchange and Sporttrade launching in New Jersey in 2022. It’s arguably a bit early to compare the accuracy of sports prediction markets to that of listed odds at traditional sportsbooks.

But either way, Crane sees those odds and prices as highly informative regarding what the most likely future “truth” is.

“If you’re curious about who’s going to win tonight’s basketball game,” he said, “then your best insight into that is to look at what the sportsbook prices are, what the Betfair price is, and so forth.

“It comes back to the idea that markets tend to be efficient, they tend towards efficiency. In other words, they’re not necessarily perfectly efficient. But for the most part, they’re the best thing we know, and the liquid markets tend to be more accurate than illiquid markets. Markets or bet types offered by sportsbooks that are getting heavily bet will be more accurate. NFL games are going to tend to have better pricing, or sharper pricing, than a bet on a women’s badminton game or something.”

Prediction market marketing 101

The majority of the conversation around sports event contracts at prediction markets this year has focused not on their accuracy, but rather their legality. Kalshi is regulated by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), which is allowing the operator to offer action on sports, but numerous states have pushed back and court filings have been flying back and forth.

“There’s a very real policy argument here on behalf of the regulated sports betting operators that, if you’re paying $25 million for a New York license and you’ve got Kalshi out here basically offering an alternative product that looks very similar to a consumer, you’re gonna be pretty ticked off,” said Holden. “You have to question, ‘Why am I paying for this?’”

Kalshi pays licensing fees of its own to the CFTC, but would not disclose to InGame just how much those fees amount to, and the CFTC did not respond to our request for the same information. Still, one can safely assume the cost of licensure in numerous states for a regulated sportsbook far exceeds the CFTC’s fees that cover all 50 states at once.

Until the day arrives when the likes of DraftKings and FanDuel have their own CFTC-regulated operations, it’s obvious why the licensed sportsbooks have shown resistance to the Kalshis of the world offering a competing form of sports betting.

And it’s obvious why Kalshi wants to offer its form of sports betting, as that has rapidly risen — at least in a non-election year — to represent more than three-quarters of the company’s trading volume.

Markets tend to be efficient, they tend towards efficiency. In other words, they’re not necessarily perfectly efficient. But for the most part, they’re the best thing we know, and the liquid markets tend to be more accurate than illiquid markets.

— Harry Crane

Zitzewitz doesn’t consider himself a sports person and is far less interested in putting money into these sports markets than he is in other prediction markets, but “I understand that that is really helpful to the business,” he said. “And it’s also great for bringing people to the marketplace, because once people are there for sports, then they are going to trade other things, including things that I think are a little bit more economically useful.”

In the end, Mansour is running a business, and sports can attract people to that business — as can making bold proclamations about prediction markets being our “quintessential truth machines.”

“Look, he’s CEO of the company,” Holden said. “So, some of this is marketing. Some of it is selling the product. And some of it is sort of extrapolating on the uses of prediction markets historically and basically isolating strong examples and trying to say, ‘This is what it’s like all the time.’”

Added Crane: “When Mansour is saying what he’s saying, in the way that he’s saying it, to a large group of people who maybe have never engaged in sports betting in a very serious way, or have never thought about sports betting prices as being a reflection of what’s likely to happen — as opposed to those who just say, ‘I’m gonna bet on tonight’s game,’ and then go ahead and bet it — it gives people a different perspective on what these markets are and how these markets work. So, as someone who prefers the exchange model to traditional sportsbook odds, I’d say the way he talks about it is a good thing. Maybe it attracts different people to get involved.

“I find the use of the term ‘prediction market’ annoying. Everyone knows it’s a form of sports betting, and they’re just doing everything in their power not to admit they’re sports betting. But it’s a better model. The operator is not competing against its customer. So, whatever you think of the ‘truth machine’ claim, it’s a good thing if it’s promoting these opportunities for bettors.”