If prediction markets continue to operate and become the “new normal,” it will be much harder to shut them down, panelists said Wednesday on the webcast “New Normal: Who Regulates the Regulators? The CFTC and the Future of Gaming Exclusivity.”

And the Brian Quintenz Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) confirmation hearing didn’t offer much hope.

“What did you think about the idea that tribes could do this, too?” moderator and Indian Gaming Association Executive Director Jason Giles asked about tribes getting into prediction markets.

“Don’t worry that your sovereignty is being violated, just break the law, too,” California Nations Indian Gaming Association Chairman James Siva quipped, referring to comments Quintenz, Trump’s nominee to head the CFTC, made Tuesday.

“Nothing in the CEA [Commodity Exchange Act], that I’m aware of, prohibits, or affects, the opportunity of tribes to offer those products and those markets and those services,” Quintenz said. There’s also likely nothing that “prohibits or affects” states from offering such markets, as well.

‘Ties to the administration’ complicate issue

To recap, prediction market Kalshi, which is registered with and regulated by the CFTC as a Designated Contracts Market (DCM), has been offering sports event contracts since just before the Super Bowl, and election betting contracts since last fall. The company’s move into offering sports-event contracts has caused much consternation in the legal sports betting industry, particularly within Indian Country.

Under the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act, tribes across the U.S. have the right to Class III gaming exclusivity if they compact for it with states. But prediction markets are licensed and regulated by a federal agency, meaning they are currently available in every state.

Prediction markets can “self-certify” markets they wish to offer, and Acting Chair Caroline Pham in late May told a group of tribal representatives that in its 50 years of existence, the CFTC has never denied or put a hold on a suggested market.

Tribal leaders are not just concerned about the challenges to exclusivity and sovereignty, but they believe that Kalshi’s connection to the Trump administration will make the issue of curtailing sports-related contracts on prediction markets a non-starter. President Donald Trump’s son, Don, Jr., joined Kalshi as a “strategic advisor” in January. And Quintenz is currently a Kalshi board member.

Tribal leaders have had prediction markets on their radar since late last year and have been working to educate Indian Country as a whole. But the process is challenging — and fraught.

“A lot of tribes haven’t heard about this … this is an incredibly important issue and we need to keep working on it,” Siva said. “I think we are going to get very little movement on this, especially after the confirmation hearing. The ties to the administration, they are impossible to ignore after the confirmation hearing.

“If we’re not going to get movement with this iteration of Congress, then we just have to stay on this. … My concern is if they are in the market for too long, it will be harder to get rid of them. And it will change from us advocating for more regulation … to something being taken away.”

Another front on which to defend sovereignty

The challenge is not new to Indian Country, which has fought to maintain exclusivity since IGRA was passed in 1988. Most recently, tribes have been fighting to keep sweepstakes platforms involving casino-style games and sports betting at bay. Those platforms are operating in an unregulated gray space, while several states, including New York most recently, have issued cease-and-desist orders demanding that numerous platforms stop operations within the state.

In some states, like California, Minnesota, and Oklahoma, where online sports betting is not yet legal, the concern is that these games and contests will become entrenched before tribes can offer legal, regulated gambling platforms.

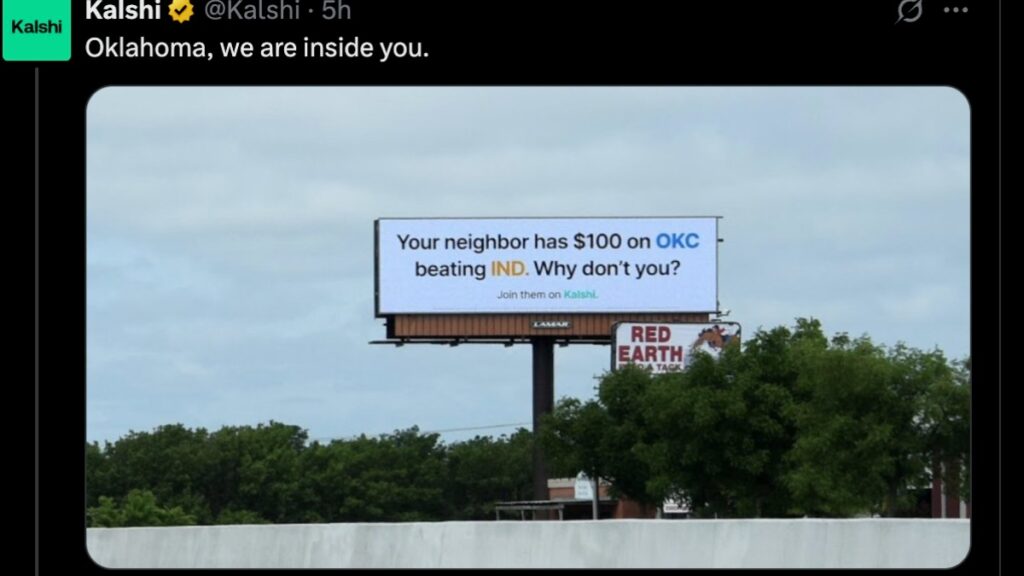

In Oklahoma, where digital wagering isn’t legal, Kalshi apparently has billboards encouraging action on the NBA Finals. The company, however, removed the post below from X that had appeared on its feed Wednesday.

“Are we going to become a modern fighting group?” host Victor Rocha, also the conference chair for IGA, asked. “The landscape has changed. Our allies have changed. What are we going to do? There are going to be some tribes who will jump on and do this. And we have to make sure that we understand the issue because every grifter out there” is going to come to the tribes wanting in on digital gambling dollars.

The panel also pointed out that prediction markets are not just encroaching on tribal sovereignty — states are also at risk. So far, there are lawsuits in Maryland, Nevada, and New Jersey involving Kalshi and Crypto.com. Federal courts in Nevada and New Jersey have already upheld Kalshi requests for preliminary injunctions to continue to offer sports-event contracts during the pendency of the cases. All three states, as well as Arizona, sent the company cease-and-desist letters. And in Nevada, the court denied the state’s motion to dismiss the Kalshi case altogether.

Giles said he was surprised that there were no questions about violating state sovereignty during the confirmation hearing, particularly since he said that was a key part of Trump’s election platform.

Don’t expect DraftKings, FanDuel to jump in fast

Regardless of how we got here, the panel said, the real questions are around what comes next. Siva has previously voiced concerns that commercial operators like DraftKings and FanDuel will pursue a pathway into the state via prediction market platforms. California tribes continue to work on an initiative that will legalize sports betting, but prediction markets and sweepstakes are already available in the state.

“The core issue is that ability to bet on sports, the encroachment of trading on sports events,” said James Kilsby, chief analyst and VP Americas for VIXIO Regulatory Intelligence. “It looks likes sports betting, but it’s not. The other is betting on other events. I don’t think we would be talking about that as a violation of tribal and state sovereignty … because novelty events, there is not a lot of money to be made, other than presidential elections. Generally these are brand-promoting exercises by betting operators. You get a lot of newspaper column inches and clicks, but there isn’t really the precedent for politics and novelty betting to take a big share of the market.

“Until we get more legal clarity, I don’t see FanDuel and DraftKings jumping into a market where they could get onto the wrong side of the regulators who license them.”

Both companies — the market leaders across the U.S. — have indicated an interest in adding prediction markets to their menu. DraftKings in March applied to the National Futures Association (NFA), but ultimately withdrew its application. FanDuel parent Flutter already operates betting exchanges in other parts of the world, and CEO Peter Jackson has said the company is “monitoring” and exploring options in the U.S. But for any company with a wagering license in the U.S., running afoul of state law and jeopardizing a license is a concern.

In the biggest picture for Indian Country, the worry is that prediction markets will become so entrenched, it will be difficult to remove them from the gambling landscape. So far, no tribes have sent cease-and-desist letters to Kalshi nor have they become involved in any litigation. But Giles said there is a plan to file an amicus brief in the New Jersey case. Tribal sources previously said members of Indian Country are considering cease-and-desist letters and other kinds of legal intervention.

“This could be the new reality. … It could hold sway,” Kilsby said. “The CFTC isn’t going to stop it. Do we see Congress stepping in? Not likely. And court battles have been very positive for Kalshi so far. So the momentum is behind Kalshi.

“There is still a long, long way to go, and it makes sense for tribal interests to be fighting this, but what happens if you lose?”