If U.S. District Judge Jacqueline Corley could rule on the motion for a preliminary injunction against Kalshi in the Blue Lake Rancheria et al v. KALSHI INC. et al case based on morality, it seemed clear Thursday that she would side with three tribes asking to ban the platform from their land.

During a more than 90-minute hearing in which she heard from lawyers representing Blue Lake, Chicken Ranch Rancheria of the Me-Wuk Indians, and Picayune Rancheria of the Chukchansi Indians, as well as defendants Kalshi and Robinhood, Corley repeatedly circled back to this question: Why doesn’t Kalshi just back down and stay off Indian land?

Among her musings in open court:

“There have been enough fights in our country with the Indians, and maybe we don’t need any more.”

“I think your client should think about it. They’re not asking for much. Tribes are sovereign, so why?”

“I can’t just sit here and think why Kalshi is doing this even if the tribes don’t want this. Maybe you’re right,” she said to a Kalshi lawyer, “but just because you’re right doesn’t mean you should.”

In July, the three tribes filed a motion in U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California to stop Kalshi from offering sports event contracts on their land, saying that Kalshi is violating gaming exclusivity by offering sports event markets on the reservation. Under the federal Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA), tribes have the right to offer gambling on their land, and in California, gaming tribes are compacted with the state for exclusivity. Every federally recognized tribe in the U.S. is its own sovereign nation.

Kalshi in court all over US

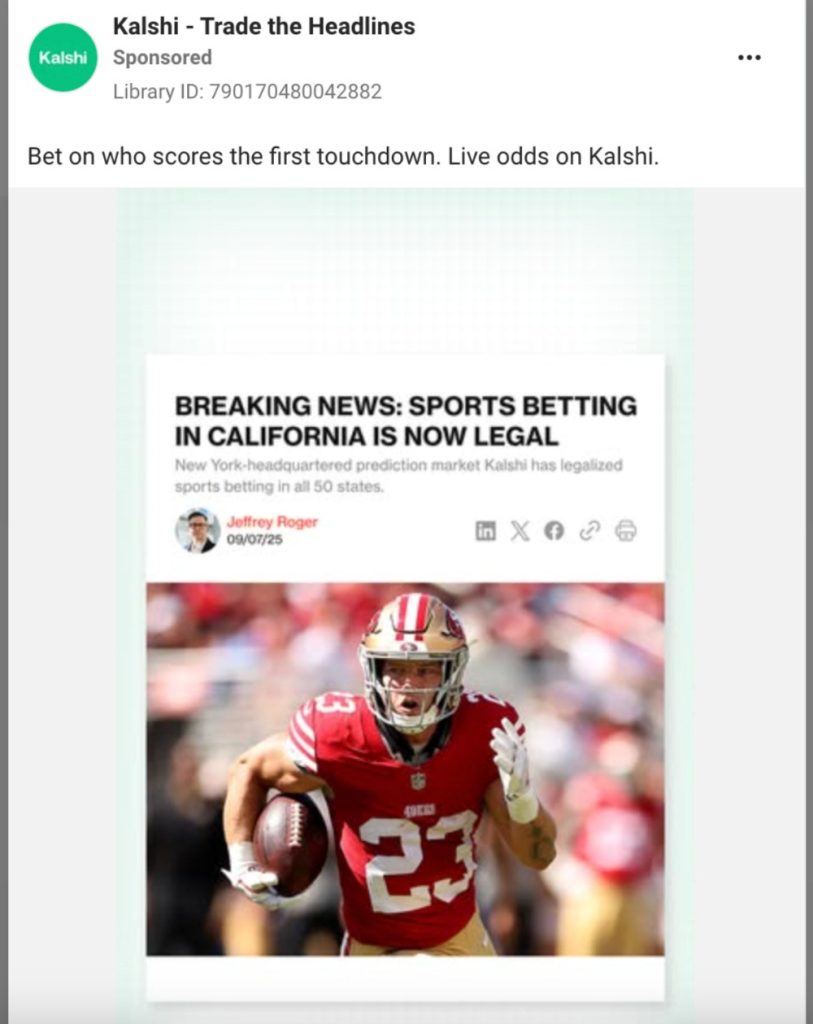

The case was the first in which a tribe or state sued Kalshi, which itself has brought federal lawsuits against the states of Maryland, Nevada, and New Jersey after regulators in each of those states sent the company cease-and-desist letters. Since Kalshi in January began offering sports event contracts, which mimic traditional sports betting, the gambling industry has been fighting back. State and tribal regulators say that even though Kalshi’s contracts are, by definition, financial tools, the company is advertising its wares as betting. And when the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act in 2018, betting became a states’ rights issue.

States and tribal regulators argue that Kalshi and other prediction markets are not beholden to the same kinds of regulations or tax structure as traditional sportsbooks, and that the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) is ill-equipped to oversee the companies offering these contracts. Those companies self-certify new markets, and the CFTC has not pushed back since the number of sports event markets have proliferated.

But like any other judge — federal, state, or local — Corley will not ultimately be able to rule based on what she believes is right. Rather, she’ll have to consider the letter of multiple laws to determine if Kalshi and futures commission market (FCM) partner Robinhood should be allowed to continue to operate on the three reservations. Corley did not offer a binding order Thursday, and there is no specific timeline for when she must.

The Wisconsin Ho-Chunk Tribe has a similar case pending in the Western District of Wisconsin. And in Massachusetts, the attorney general sued Kalshi in state court seeking the right expel Kalshi from its borders.

There are conflicting opinions that Corley can refer to — in Nevada a district court judge ruled that Kalshi can continue to operate, but that Crypto.com cannot, and in a case against Maryland, the Fourth Circuit ruled that Kalshi must shutter, though the state agreed to allow it to continue to operate until the case is resolved. In New Jersey, a district court judge ruled that Kalshi could continue to operate, and the case is now with the Third Circuit after the state regulator appealed.

Sovereignty, exclusivity top of mind

At issue in both states and Indian Country is what, exactly, sports event contracts are. Defined as financial tools by Kalshi and others, the product consumers see bears a strong resemblance to traditional betting. Judges across the country will have to determine if the products are ultimately defined as gaming, which the Commodities Exchange Act (CEA) bans. Most stakeholders believe the Supreme Court will be the ultimate arbiter on that issue.

The CEA explicitly defines commodities that range from oats and barley to livestock and concentrated orange juice as well as “motion picture box office receipts.” Sports events are not mentioned anywhere in the law, and the CEA gives the CFTC the power to ban contracts on “gaming, war, terrorism, and assassination.”

While the question of what Kalshi is offering is in play in the tribal case, it was clear from Corley’s line of questioning that she sees key issues as being tribal sovereignty, the gaming exclusivity that California’s tribes have via state compacts, and which federal law prevails in the discussion.

Tribal lawyer Lester Marston told Corley that “this is not about trading, this is not about commodities. … As far as I am concerned, this is an issue of tribal sovereignty, it’s an issue of gambling. They are illegally gambling on our reservations.”

Kalshi attorney Grant Mainland of Milbank LLC said in his rebuttal that Marston would have the judge “look at IGRA and you look at IGRA alone, you put on the blinders and pretend that other statutes don’t exist. But that’s clearly not the case.”

When it comes to Indian gaming and prediction markets, judges must decide if IGRA preempts the CEA or vice versa. Several other federal laws must be considered, as well, including the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act (UIGEA) and the Wire Act. But the lawyers and Corley spent limited time on either of those, focusing instead on IGRA, the CEA, and the West Flagler decision, which gave the Florida Seminoles a monopoly on digital betting both on an off the reservation. The Seminoles’ compact with the state of Florida includes language that allows a bet to be considered placed where received, and every legal online bet in Florida flows through a server on tribal land.

The California tribes aren’t asking for the right to offer betting off reservation, which is illegal in the state. Rather they want to control what is happening on their own lands, causing Corley to posit that the case is “the opposite of West Flagler.”

Tribes lose if bettors wager on Kalshi

In discussing how allowing Kalshi to operate on tribal lands when tribes can’t legally offer the same product would hurt the tribes, Marston said that those who view gambling as entertainment often earmark a set amount to gamble. Should they choose to use those dollars on Kalshi, they won’t be spending them at a tribal casino.

“As a result of deception,” Marston said in reference to Kalshi advertising that it offers legal betting in all 50 states, “they are spending it not on the reservation.”

Corley appeared to agree, saying “if you use money to gamble on the app and not come to the casino, that is harm.”

Kalshi lawyer Mainland said that in traditional sports betting, commercial operators win when players lose, but that on Kalshi’s platform, the company is “indifferent to the outcome, it’s the traders trading amongst themselves.” He went on to say that Kalshi’s goal is not to “undermine sovereignty, it is to run a business.” Later in the hearing, Kalshi’s Olivia Choe said she did not believe that the tribes had effectively shown that their revenue streams would be damaged by Kalshi and argued that prediction markets aren’t just trying to make a buck.

Mainland also said that while the case is being brought by three tribes, that there are 584 tribes in the U.S., so the case could be a gateway to more. He also suggested that geofencing all those tribes could cause a hardship to Kalshi.

Tribes need gaming money to survive

Marston emotionally argued that IGRA unequivocally allows tribes to decide what is or is not acceptable gambling on their land, and that in tandem with the California compacts, require any gambling on reservations to be approved by a tribe. None so far have welcomed Kalshi. He also argued that the whole point of IGRA was for tribes to become self-sustaining, and that proceeds from gaming are used to support tribal communities, including funding health care, education, elder care, first responders, and more.

“Gaming dollars are used for necessities on the reservation,” Marston said. “We’re not like Kalshi, we’re not in business to just make money. All the money goes to the [tribal] government.”

Marston said Kalshi is violating Section 27.10 of IGRA, which explicitly says that the only gaming allowed on a reservation must be approved by both the tribe’s governing body and legal in a state. Kalshi, which is regulated at the federal level, does not have explicit approval from either.

Corley asked why the tribes did not take their issue to Attorney General Rob Bonta, and Marston said he’s tried, but got no relief. Bonta’s office is currently dealing with at least two other gambling-related issues in which the tribes have an interest — rewriting regulations for the state’s cardrooms and crafting enforcement action against daily fantasy operators after offering his opinion in July that those platforms are illegal.

Corley appeared to want to hear more from Marston than Kalshi’s or Robinhood’s lawyers. When they did have a chance to speak, Corley cut them off multiple times, saying more than once that she understood the legal issues, and was more interested in the moral ones.

“Why is Kalshi insisting, it’s not much land or people, you can geofence,” she said near the end of the hearing. “Why is Kalshi pushing?”

She continued: “I’m not asking a legal question, I’m actually asking a more moral question. … I’m actually asking your client, who I hope is here, to step back, to pretend to be a human being, as opposed to an entity making money, for a second. … These three tribes are saying ‘we want to govern our land, we don’t want this to be there,’ you heard why. Maybe just think about, maybe ‘we don’t need this extra little tiny bit.’ … I want your clients to think that maybe we don’t need to go into this fight, and we can do it some other way.”