Oral arguments in Kalshi’s lawsuit against New Jersey appeared to go the way of the prediction market, according to lawyers observing the proceedings, as a judge suggested the laws around financial “swaps” appear broad enough to include sports bets, and if that needs to be changed then it should be the job of Congress to sort it out.

Counsel for Kalshi and the state of New Jersey were arguing Wednesday before the Third Circuit Court of Appeals and its panel of three judges: Chief Judge Michael A. Chagares, Justice David J. Porter, and Justice Jane Richards Roth.

The Third Circuit case was brought about when New Jersey appealed a decision in the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey to grant an injunction that prevented the state from enforcing a cease-and-desist against Kalshi’s sports event contracts, in which users can stake money on sporting outcomes.

States have argued that these contracts are illegal under their own gambling laws. Kalshi argues that they are not, as it says that under the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA), only the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) has jurisdiction over contracts offered by a designated contract market (DCM). Much of the case depends on the exact circumstances in which federal law “preempts” state law.

Swap definition is ’broad’

After some initial discussion between the judges and counsel about the correct pronunciation of Kalshi, New Jersey’s lawyer Steven Ehrlich began by arguing that Kalshi’s contracts are not truly swaps — a type of financial product regulated by the CFTC — because their links to an economic consequence are too tenuous.

But at least one judge appeared skeptical of Ehrlich’s argument, noting the wide-ranging definition of a swap in the law. According to the 2010 Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, a swap must be “dependent on the occurrence, nonoccurrence, or the extent of the occurrence of an event or contingency associated with a potential financial, economic, or commercial consequence.”

Judge Porter argued that this definition seems broad enough to include a wide range of events.

“It seems that the definition of swap is quite broad. I understand you point out some things that seem undesirable to your side, you suggest something should be inherently, financial, economic, whatever, but that’s not in the statute,” he said.

“Aren’t we obliged to apply what the elected branches have gotten us here, and to the extent any fix is necessary — and we’re not saying it is — isn’t that for the elected branches to deal with and not us?”

Ehrlich argued that there must be some sort of limit on what counts as a potential economic consequence of an event, and said that counting the Super Bowl as having economic consequences because of the winning team’s parade — as Kalshi has argued in its briefs — was “too attenuated.”

“I agree it’s broad and it’s because Congress was trying to sweep in various things as part of the Dodd-Frank reforms,” Ehrlich said.

“They couldn’t foresee exactly what would become a swap, but it’s not unlimited.”

’Certain player props’ may not be swaps

When Kalshi’s lawyer William E. Havemann spoke, judges pressed further on the question of what the limit should be on what counts as a potential economic consequence of a swap.

Chagares gave the example of a table tennis match between himself and Porter, which “may be of interest to the clerks.” Havemann said this would likely not qualify as having economic consequences.

Asked by Porter for an example of a sports contract that would not qualify as a swap, Havemann said, “There are probably certain player props that would not meet the definition.”

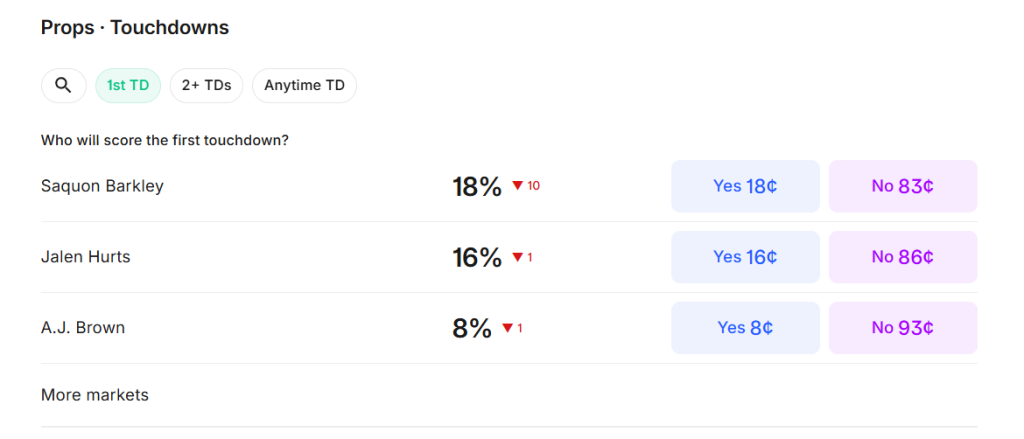

Kalshi currently offers player props on NFL touchdown scorers, and has offered parlay bets that also include touchdowns as a leg. However, it has not offered props related to other player stats, nor has it offered props outside of the NFL. Havemann did not elaborate on what type of player props may not count as swaps.

In his rebuttal, Ehrlich argued that Kalshi’s attempts to draw a line were not based on the text of the law itself.

“I don’t see any limiting principles,” he said. “The ones they have pointed to are atextual.

“There is no actual limit to what counts as a consequence here.”

NJ: Kalshi would make all casinos criminal

Ehrlich also warned of the wider consequences of Kalshi’s interpretation of the law, which he said would mean any sportsbook and casino would be guilty of offering unregistered swaps.

“That would make all casinos and sportsbooks criminal enterprises,” he said.

However, Havemann dismissed this idea as a “parade of horribles,” suggesting that the supposed consequences of Kalshi’s interpretation of the law were not real. He said that federal law would only be preempted in the specific case of trading on a CFTC-registered designated contract market.

“The key statutory distinction that Congress has drawn is that if it’s on exchange, it’s subject to the CFTC’s jurisdiction; if it’s off exchange, Congress can regulate it,” he said.

However, Ehrlich argues that provisions of the CEA make it illegal to trade swaps outside of a registered exchange, meaning that this interpretation was not possible.

“I have no idea what they’re talking about when they say, don’t worry, this can only be limited to designated contract markets,” Ehrlich said. “That’s not how the statute works.”

Judge says lower standard applies

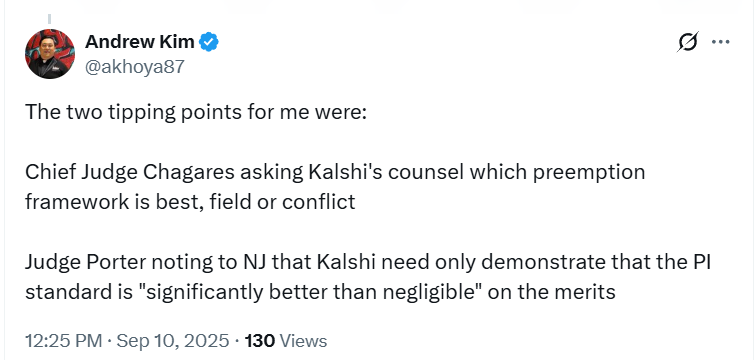

One key signal that the judges may be inclined to rule Kalshi’s way was a discussion of the standard necessary to do so. Judge Porter said, based on the fact New Jersey is challenging a preliminary injunction that prevents the state from enforcing a cease-and-desist, Kalshi would not necessarily need to prove that it is likely to win the case on the merits in order to have the injunction upheld. Instead, he said, the prediction market just needs to show “that they have a significantly better than negligible argument.”

Porter appeared to believe there was a good chance Kalshi could meet that standard, asking Ehrlich, “Are you saying that the position is not significantly better than negligible?”

Ehrlich said that although he felt the judges should side with New Jersey by “any standard,” the case was a “pure question of law,” and therefore should be a “de novo review.” That would mean the case would be heard without any deference to the District Court’s decision, as if it is a brand new case instead of an appeal, in which case the standard would be whether Kalshi is likely to win on the merits.

Porter didn’t offer any further comments to signal whether or not he was convinced by those arguments.

Conflict vs. field preemption

The court also may have suggested that there were two paths toward a ruling in favor of Kalshi: field preemption and conflict preemption.

Field preemption refers to the idea that a federal law “preempts the field,” or, in other words, supersedes all state laws about that given topic. That is the principle that the District Court used to rule in favor of Kalshi. There is little doubt that the CEA preempts the field of commodities regulation, but the parties in the case disagree on whether this would also apply to sports betting-style contracts on a designated contract market.

However, even if field preemption does not apply, Kalshi has also argued that the principle of conflict preemption could be appropriate. According to Congress.gov, “conflict preemption occurs when compliance with both federal and state regulations is impossible or when state law poses an ‘obstacle’ to the accomplishment of the ‘full purposes and objectives’ of Congress.”

In this case, Kalshi says it would be unable to comply with New Jersey gaming laws, arguing that it would then be required to “accept bets only from people in the state of New Jersey.”

Ehrlich said this wasn’t the case, and a New Jersey-licensed Kalshi could still accept bets from customers elsewhere.

Chagares appeared to be considering both the conflict and field arguments, asking Havemann which of the two was the more appropriate principle at stake.

Lawyers felt day went Kalshi’s way

Lawyers following the case largely felt that proceedings went well for Kalshi.

Joe Webster, a partner at Hobbs Strauss who has acted on behalf of a group of 60 tribes and eight tribal organizations in their amicus brief in support of New Jersey in the case, said the oral arguments and judges’ reactions did not make him confident the District Court decision would be overruled.

“We have our work cut out for us,” he said during a panel at the Indian Gaming Association Mid-Year Conference in Minnesota. “The questions were more skeptical of the state of NJ than of Kalshi.

“It’s really hard to say that I’m confident that they are going to reverse the lower court.”

Andrew Kim, a partner at Goodwin Law, wrote in a thread on social media site X, “I’d rather be Kalshi than New Jersey.” He said the backstop of conflict preemption could end up being key to the case.

He added that Porter and Chagares “were, at various times, nodding along to what Kalshi’s lawyer had to say. I don’t think the judges were buying New Jersey’s hyperbolic ‘everything’s a swap’ argument at all.”

The third justice in the panel, Judge Roth, attended remotely and asked no questions, making her views about the arguments harder to discern.

Other Kalshi lawsuits

Kalshi is involved in two other lawsuits against states. In April, the U.S. District Court for the District of Nevada granted Kalshi an injunction similar to the one in New Jersey. Unlike in the New Jersey case, the injunction was not appealed to a higher court. Last week, a judge ruled that the case would require discovery, which could mean Kalshi would have to present all of its communications with the CFTC.

Last month, the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland ruled in the opposite direction to New Jersey and Nevada, denying the request for an injunction. That decision was quickly appealed to the Fourth Circuit.

Federally recognized tribes in California and Wisconsin are also suing Kalshi, arguing that sports event contracts violate the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA). Unlike the state cases, the tribal lawsuits deal with the conflict between two federal laws: the CEA and IGRA.