The 109 Native tribe gatekeepers of gambling in California appear closer than ever to determining what digital sports betting will look like in that coveted, untapped legal betting market.

But that doesn’t mean they’re close.

Various estimates peg a mature California sports betting market to be worth as much $6 billion in revenue in the nation’s most populated state and world’s fourth-largest economy. So the tribes continue to negotiate among themselves to find a pathway, and commercial operators continue to keep the lines of communication open. In California, the when and the how of any expansion of gambling must run through the tribes, who have exclusivity.

The rift that opened between Indian Country and the industry during and after the 2022 California wagering initiative campaign has started to close. Or at least it has gone from chasm to crack. There’s still distance, but there has been progress.

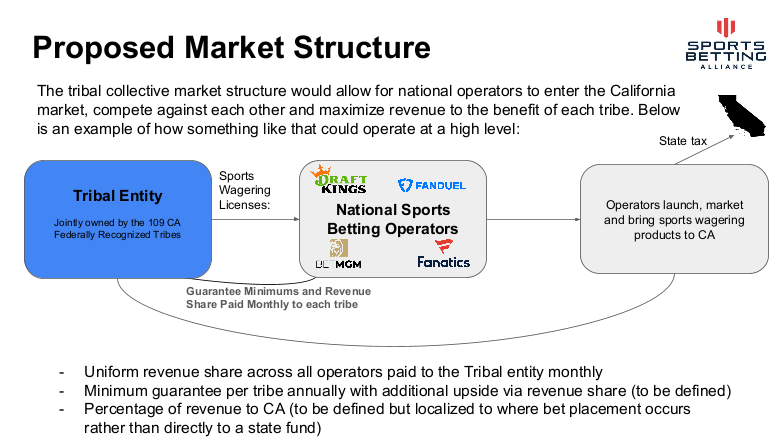

In March, the Sports Betting Alliance (SBA) — comprised of BetMGM, DraftKings, Fanatics, and FanDuel, with more companies expected to soon join — presented a proposal to tribal leaders at the Indian Gaming Tradeshow & Convention in San Diego.

Next up: A working group of tribal lawyers is expected to present its own plan to California Native leaders June 2 in Sacramento.

No one knows what new ideas or potential solutions will emerge. But whatever does, this will remain a lengthy process. Tribal leaders say they won’t field an initiative to amend the state constitution and legalize sports betting before the 2028 election. But 2030 is also a possibility.

Until then, the negotiation for tribes remains deeply about sovereignty, self-sustainability, and defending the exclusive right through the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act and California Constitution to offer gambling. There remains a lingering distrust of the national sports betting operators who have sought for years to do business in the state either with the tribes or despite them.

Memories of 2022 initiative promises have created suspicion over the SBA’s proposed new super-sized payouts to the tribes. As part of Proposition 27, which was funded predominantly by FanDuel and DraftKings, there was a promise to funnel significant funding to fighting homelessness in California.

This time, in exchange for the right to launch their sports betting apps in the state with tribal acquiescence, the SBA in March pointed to help closer to home. Currently, the biggest Native casinos send money to the RSTF, and it is distributed to 72 non-gaming or small-gaming tribes. The $1.1 million per tribe stipend has remained stagnant since 1999.

SBA representatives said that if they are allowed to operate branded platforms in California, they are committed to sending at least $10 million per year to each of the 109 tribes by the third year of a deal. The payments would commence at $5 million in the first year and increase to $8 million in the second before reaching the $10 million minimum.

For the RSTF tribes, it would be a life-altering salvation. Others see that inducement as a way to dilute tribal unity.

“I think that’s the new carrot on the stick. How is that any different from promising they were going to solve homelessness? Or building new houses?” Pechanga Resort Casino President Sean Vasquez told InGame, noting that he’s not involved in negotiations.

“It’s just the next thing and a new gimmick to try and lure people in and break apart a consortium and a unified mind. It’s entirely frustrating to the process. And I don’t think it’s conducive to actually making headway in the space.”

This isn’t new, Jacob Coin, executive advisor to and chairman of the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians, told InGame.

“Any time tribes had something of value, somebody was coming up with ways to take it away,” he said. “This may be the very last significant right, something of value that tribes have. So we have to guard it jealously.”

Tribal gaming was a $41.9 billion industry nationally in 2023, with a quarter of that generated in California.

It’s just the next thing and a new gimmick to try and lure people in and break apart a consortium and a unified mind. It’s entirely frustrating to the process. And I don’t think it’s conducive to actually making headway in the space.

— Sean Vasquez, Pechanga Resort Casino president

Tribes are talking, and that’s meaningful

Finding consensus in 109 of anything is difficult. But tribal leaders who gathered at the SBC Summit Americas 2025 this month contend there is the potential for it. And a united Indian Country, they said, is vital in together controlling and benefiting from this latest very “valuable thing” outsiders have come onto their lands to negotiate for or take.

“That they’re talking among each other and with the SBA is telling,” Jesus Tarango, tribal chairman of Wilton Rancheria, told InGame.

“There’s a lot of open conversations now,” he said. “It’s funny because people are like, ‘How’s the relationship?’ I said, ‘Well, when tribal leaders are talking, you may not want to hear what they’re saying. But if they’re talking to you, it’s for a reason.’

“If I don’t want to talk to you, I won’t talk to you. And so for that, I think we’re really moving in the right direction.”

When tribal leaders are talking, you may not want to hear what they’re saying. But if they’re talking to you, it’s for a reason.

— Jesus Tarango, Wilton Rancheria chairman

Every California tribe has been invited to hear the plan developed by a group of tribal lawyers, Tarango said. There had been speculation after the SBA unveiled its proposal in March that California tribes were amenable to at least parts, especially a tribal syndicate serving as the licensee and regulator in the state. That said, there’s no guarantee what amount, if any, of the SBA plan could land in a tribal blueprint.

“I think it’s hard to get even four people aligned on one thing. But you can agree on four or five principles, right? And I don’t think anybody can disagree that the equity of 109 people should have a say,” Vasquez said. “And I think tribes like mine [that] are a little bit bigger, we are trying to fashion a model that gives all 109 people equity. Not just one, two, three, or four picking winners. I think the operators want to pick three or four winners and go with them.”

Before bringing the industry back into the conversation, California’s tribes must consider and massage the proposal from the lawyer’s group. Once there is consensus inside Indian Country about what wagering will entail, the industry could then be invited to join the discussion.

“Nobody’s being left in the dark.,” Tarango said. “We’re getting ready to get this framework so that we all hopefully start off on the same foot here.“

Meanwhile, Ari Borod, the chief business officer at Fanatics Betting & Gaming, said progress has been made in the crucial intangible area.

“I think [progress] on the relationship side, yes,” he told InGame, then added: “I think there’s a lot of trust that we need to earn with the tribes there.”

Trust, negotiations, billions of dollars

Even if the industry and California tribes find a mutually acceptable format, an initiative would be required to amend the state constitution and expand the scope of gambling in California.

That will not be a cheap process. But it could look frugal compared to the nearly $500 million spent in the 2022 Prop 26 and Prop 27 pro/con ad war.

Large casino properties like the Yaamava’ Resort and Casino, Pechanga Resort Casino, and Morongo Casino Resort & Spa, fortuitously located near Southern California urban centers, generate revenue that allows the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians, Pechanga Band of Luiseno Indians, and the Morongo Band of Cahuilla Mission Indians, respectively, to defend their interests politically.

Their fortunes funded the campaign in 2022 to initially back Prop 26, which would have legalized in-person sports betting on tribal lands and at four horse race tracks, then fight Prop 27, which would have opened the entire state to outside sports betting operators via mobile. The tribes would have been granted ball-and-dice games under Prop 27.

Both sides understand trying to legalize online sports betting from Calexico to the Smith River through the initiative process is perilous without a unified front.

Voters in seven states have approved legal wagering via ballot initiative, but none has been a runaway win. The most recent example was Missouri, where voters ultimately approved legal betting by less than 5,000 votes. And operators spent hundreds of millions of dollars on initiative attempts that they lost or abandoned in California and Florida in 2022.

Progress was apparently in motion when both sides reportedly coalesced independently around the general framework of a plan like the one the SBA presented to the Indian Gaming Tradeshow & Convention. But tribal groups were incensed when a journalist was invited to report on what they believed to be a private conversation.

Still, the SBA presentation at the event cited “guiding principles” for California legalization that mirror what tribes have demanded publicly:

- Tribal-led, tribal-driven, tribal-owned

- Protect tribal sovereignty

- Preserve tribal gaming exclusivity

- A framework that would allow all California tribes to benefit

Both sides understand that online casino has been the next ask in many states that have legalized sports betting. In California, digital sports betting will be the cornerstone on which iGaming will be built, and the tribes say online casino is not currently in play.

That figures to be an even longer legalization process, according to industry sources.

And according to a source familiar with the SBA’s thinking, the industry has told tribes it wishes to focus on sports betting, and tribes would “own the iGaming pieces” in the future.

Crucially, both legally and for the sake of negotiations, everything runs through the tribes. Having fought to reach this point on the land-based side, Vasquez said, tribes don’t intend to cede control to outsiders.

“We are the faithful stewards of gaming in California. The California voters trust us with it,” he said. “And I think that was doubled down on in the last cycle of bills. Anything that disrupts tribal leadership, tribal sovereignty, is just an outright non-starter.”

How could California sports betting look?

While both sides have so far voiced support for a Native corporation of 109 tribes that would oversee sports betting in the state, they diverge on the branding of the apps that would compete for customers.

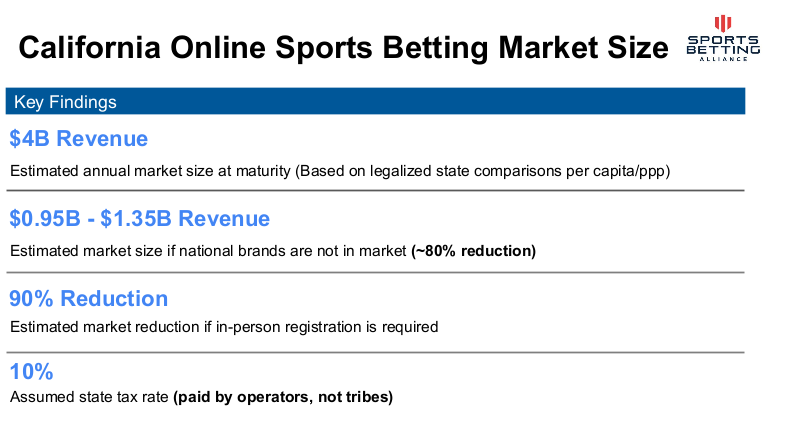

National brands tout their record of success in 41 U.S. jurisdictions and their plug-and-play ability to grow markets and contend that all sides gets richer if their well-known apps face the marketplace. An internal SBA study asserted that a California sports betting market at maturity would be worth $6.1 billion with national brands, while a tribal white-label market would top out at around $800 million.

These large commercial operators, the industry contends, would also be better equipped to handle the three-to-five-year investment-and-loss cycle often required to become profitable.

But some tribes oppose national-operator branding in California in any form, preferring that companies like DraftKings or FanDuel remain anonymous tech providers to white-label apps.

California Nations Indian Gaming Association (CNIGA) chairman James Siva said last year that national brands won’t be front facing.

“I can tell you what they won’t be,” he said. “They won’t be operators in the state. If they want to be partners like the slot companies we work with, then we can do that. I think they are starting to come around.”

While that’s not acceptable for the commercial industry, national operators are thought to be amenable to a “powered by” relationship in conjunction with a tribal app.

A source told InGame that the SBA was “not married” to any plan to the point of risking a deal and was “happy to talk about any frameworks” once a tribal plan is revealed.

Jason Ramos, tribal chairman of Blue Lake Rancheria — located 20 minutes from Eureka in Northern California — and a member of the SBA’s tribal advisory board, doesn’t think white-label apps are right for California.

“I’m not sure that I see a pathway forward where we would be able to either compete with [commercial operator apps] or develop our own,” he said during an SBC Summit Americas panel on California sports betting. “I’m sure there will be something out there and an idea that comes out. But for me, I think if you’re looking at a total regulatory and framework situation that would maximize benefits for these poorer tribes, whether they be non-gaming or limited gaming, [commercial apps are] going to be an attractive path forward because revenues are going to be so good with those established operators.”

Still, some industry observers have been skeptical of a system that they believe insulates tribes from all those new California customers.

“There’s a wonderful graphic: tribal entity over here, the customer’s over there, and in the middle is the SBA,” Gene Johnson, executive vice president of Victor-Strategies, which consults on native gambling issues, told InGame. “That’s the crucial point. Any business would be rather crazy to allow access to their customers only through a third party.”

There is room for compromise, Vasquez said. But not on one crucial point.

“I don’t believe we’re categorically against commercial partnerships,” he explained. “I think [national operators] have to be more in line with working with us and how it’s going to roll out and how we can manage that in terms of syndication.

“Because you don’t have commercial gaming in [California], there needs to be tribal leadership on this initiative. That’s what I think needs to be recognized. Not tribal participation. Tribal leadership. You have to have some sort of focus on helping all 109 tribes to uplift them.”

FanDuel and DraftKings have lobbied hard in Indian Country, especially among smaller, less-monied tribes. The companies expect the prospect of enriching the monies that tribes receive to be popular for the tribes that struggle to subsidize basic needs.

There needs to be tribal leadership on this initiative. That’s what I think needs to be recognized. Not tribal participation. Tribal leadership.

— Sean Vasquez, Pechanga Resort Casino president

It’s potentially a public relations win for the national gambling industry and a way to increase an annual RSTF payout that a complicated state-level procedure has thwarted.

But the industry tried a similar path in 2022, and three small, rural tribes lobbied for the commercial initiative. The move divided Indian Country, and tribes are now aiming to craft their own way to lift smaller tribes from poverty rather than take that direction from outsiders.

Do Californians really want legal sports betting?

The tribes and national operators differ in their read on the state’s appetite for legal sports betting. The SBA presentation at the March event cited polling “based on 10 focus groups in California and three statewide surveys” that showed 64% were either “somewhat” or “strongly” in support of legalized sports betting there.

Wording is crucial. According to an SBA source, when framed as a way to combat black-market sports betting, benefit tribes, and boost tax coffers, polling increases to 72%.

A tribal source said the public is less enthusiastic about legalization now than before Propositions 26 and 27 failed. Because of that — and other issues — Indian Country isn’t ready to run an initiative.

Tribal gambling revenue funds key projects

Exclusivity and economic sovereignty have underpinned the tribes’ arguments since the beginning. Economic parity between them has been a harder proposition. Those whose lands are near population centers were able to build large and successful casino properties while smaller, more remote bands had no such lucrative lure. Revenue from mobile sports betting would help offset that.

For smaller tribes, some of whom don’t offer gambling at all or do so on a much smaller scale, financial stability is still tied to the success of their bigger gaming counterparts because of the RSTF.

The Wilton Rancheria tribe was not federally recognized from 1958 to 2009 and was a fund recipient until it opened a Sky River Casino 25 minutes from Sacramento in 2022. Managing a tribal government isn’t easy on the RSTF stipend, Tarango said.

But, he said, “I think it’s going to be fine, man,” because he sees legalizing digital sports betting as a way to address the unaddressed economic disparity for those disadvantaged by real estate.

“That’s where all of us can be one,” he said. “I know tribal leaders 2½ hours away from any cities or anything. And the only reason why we’re so successful is because I’m right off a major highway. But what makes me better than them?”

Sports betting represents a “new bucket,” Tarango said, that can elevate all and perhaps fix years of acrimony since an initial 58 tribes negotiated Class III gambling compacts with then-Gov. Gray Davis in 1999.

“This has to be an equal share for everybody,” Tarango said, “because there’s been 20-plus years of bad blood between tribes that are not gaming.

“[Non-gaming tribes] look at these big gaming tribes, and it’s like, ‘Well, we had to sign up.’ But the tribes that knew they were never gaming gave that up because [the gaming tribes] were supposed to give something.

“So if you’re that tribe that gave up that right for these tribes to now get more money, and they don’t want to give you any more money, who really lost their way? And so that’s why, for me, that’s why I take the position it has to be for all of us. It has to be for an equal share. And if it doesn’t have that in it, I don’t want any part of it.”

Vasquez said he can’t tell if tribes are being peeled away from a unified Native front. The situation, he said, is being made worse because “we’re getting some bad advice and bad-faith operators” via inter-tribal negotiations.

Previous challenges to exclusivity

California tribes were supposed to enjoy exclusivity for gambling in California forever, but banked card rooms have flourished in the state. Tribes needed the federal government and the Unlawful Internet Gambling Enforcement Act in 2006 to push out online poker.

California’s card rooms predated the compacts and offered player-banked games. This means that rather than playing against the house, one player at the table acts as the bank. In 2007, card rooms adopted a new model, hiring third-party providers (TPPs) to act as the bank. The tribes argue that using TPPs essentially makes the games house-banked.

The tribes have been vocal in saying the card rooms are violating their exclusivity, but until last fall had little recourse. As sovereign nations, they could not sue or be sued in state court. In September, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed SB 549 into law. It allows the tribes one opportunity to file one lawsuit against the card rooms.

Indian Country had until April 1 to file, but did so Jan. 2. Dozens of documents from card rooms and tribes have already been submitted, and the next court date is set for Aug. 8. The card rooms can continue to operate with TPPs, but if the court ultimately determines they are in violation of state law, they will have 60 days to stop offering the games in their current form.

Lessons learned, apologies accepted crucial for deal

California voters, besieged by nearly a half-billion dollars worth of combined negative advertising, trounced sports betting at the ballot box in 2022. The defeat left the industry marking time and leaders of national commercial sports betting giants humbly reassessing the rules for winning the biggest prize on the board.

There’s time to fix it all. But it won’t be easy.

“There’s a lot of mistrust out there from the public, from the tribal side,” said San Francisco-based attorney Baird Fogel, a partner at Eversheds-Sutherland who has negotiated energy contracts with tribes. “It’s going to be a steep hill to climb, but it’s not going to get climbed if there’s not a collaborative and trusting kind of framework established here at the outset.”

Ramos, a member of the SBA’s tribal advisory council, noted during the SBC panel that “some of those companies in the SBA on the last go-around, they tried to jump the gun.”

“I had a problem with that too, and I was on the other side fighting,” he continued. “But at some point, we have to come together, figure this thing out, make sure that it’s well-regulated, make sure the tribes have their stake in it, that we’re the regulators and operators of the industry. I’m hearing a lot of conversations between different factions within tribes, and people tend to say the same things.

“And I’m like, what are we arguing about here? Let’s find the best pathway forward, and let’s figure this thing out.”

With FanDuel notably extending its lobbying efforts deep into Indian Country to prepare for another attempt, the approach appears to have been changed, signaling to the industry the potential for conciliation.

“I think, obviously, the ballot initiative corroded some of that trust,” Borod said. “I think we’re all working very hard to regain it. I think everybody wants the same thing, which is a very healthy regulated market that appropriately compensates the local interests.

“It’s really just about continuing to build trust and relationships. That side, I’d say, is progressing nicely. What that turns into, we’ll see.”

Jill R. Dorson contributed this report.