Growing up in Lebanon, Tarek Mansour said he was a tech dummy. He didn’t know what Google, which is only two years younger than the 29-year-old, did or was. But just like the company that made up a word that is now entrenched in American culture, Mansour took a word from his native language and introduced Kalshi into the American lexicon.

“We had one shitty computer at home that barely worked,” he said in an interview with Sourcery in February. “I grew up, I never even thought that Google was a company — that’s the level of exposure I had … I was very non-entrepreneurial, I knew nothing, I just knew math.”

That naive kid, who was born in California but grew up in Lebanon until he was 17, is now the CEO and co-founder of a billion-dollar company that he and college friend Luana Lopes Lara founded in 2018.

Mansour moved back to the United States for college, studying electrical engineering and computer science and mathematics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). After graduating, he went on to work in financial trading as an equity derivatives analyst at Goldman Sachs, then later a macro trader at Citadel, and more in between.

Mansour met his Kalshi co-founder at MIT. Lopes Lara, a fellow international student from Brazil, seemed an odd pairing with him. But the two followed similar financial trading paths after college.

“It was a hard transition. Everyone was better at math than I was, but I generally like being out of my comfort zone, and in some ways I get more relaxed since expectations were lower and I could just focus on learning a lot,” Lopes Lara told InGame about starting at MIT. “I got very into finance at the start of college when I realized I liked the math side of CS more than pure coding; from there, finance just made sense.”

After a few years in the financial sector, Mansour and Lopes Lara took action on their shared interest in prediction markets and founded Kalshi. Mansour thought about the idea mathematically: Institutions care about how events play out, and people care about how events play out, so people should care about prediction markets, he explained.

“It was pretty organic. There was never a point where we were like, ‘All right, you would be a great co-founder.’ We were friends from the start and had very similar interests,” Lopes Lara said. “The idea of Kalshi organically evolved over three years, and then it just was inevitable that we wanted to try to do this and we should do this together.”

Who’s who of early investors

A year after founding the company, the duo attended Y-Combinator (YC), a three-month program designed to help startup companies take off. Kalshi got its earliest funding from YC and then from Sequoia Capital, billionaires Charles Schwab and Henry Kravis, and others. Today, Kalshi is one of Charles Schwab’s largest investments (the individual, not the brokerage that bears his name).

“They got a little bit of money to start this idea, and it took root … and they’re on their way to making a quiet little fortune. Changing things in a way that is moving things forward, I would argue,” Milbank lawyer Josh Sterling, who represents Kalshi, said at a National Council of Legislators from Gaming States meeting in July. “And that’s what we want, I think, as a country. So setting aside one’s interest in litigation, or a client, or any other such thing, I think that’s a really good thing: innovation in America, making money, creating jobs.”

Kalshi has certainly been a disruptor in the online sports betting space — and last week, the platform expanded beyond the U.S., when the company announced it had gone live in 140 countries around the world. The company also just raised $300 million in its latest funding round. Kalshi now boasts a valuation of $5 billion.

But even just a few years ago, Mansour was starry-eyed.

“I had only talked to Chuck (Charles Schwab’s nickname) for a few minutes on our first call when he said, ‘I’m going to invest,'” Mansour told European Central Station. “He said our company reminded him of when he founded Charles Schwab, and that after waiting so long, he finally saw a company that could fundamentally change the financial markets.”

However, the first few years were a struggle of securing financing and regulation. “It was brutal. It was the worst form of torture anyone could imagine,” Mansour told Sourcery. But he and Lopes Lara believed in their idea and pushed forward.

Although Mansour described himself as naive when they were first starting out, Lopes Lara said he is realistic and a steady partner.

“Tarek and I work well because we have very complementary personalities. Tarek is good at sales and going deep on one critical thing at a time, I’m better at keeping multiple balls in the air and managing the company and developing systems,” she said.

“I’m also a more optimistic person, he’s more pessimistic, which keeps our decision-making grounded in reality,” she added.

In November 2020, right as Joe Biden won the presidency, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) approved Kalshi’s registration as a designated contract market. It gave Kalshi the imprimatur of the U.S. government to operate within the bounds of the Commodity Exchange Act and CFTC rules — the contours of which are currently the subject of substantial debate.

Kalshi took off from there and is now used by thousands of Americans every day to trade, or bet, on everything from orange futures to presidential elections to sporting events. The company handled $2.86 billion in volume in September, 90% of it on sports event contracts, per Susquehanna.

Mansour told Sourcery, “I would never have imagined any of this.”

Regulation and sports betting

Since introducing sports to its platform in January, Kalshi’s CFTC regulation status has made it the subject of many debates, multiple lawsuits, and growing scrutiny from state regulators looking to protect their states’ financial interests and constituents.

In contrast to traditional sports betting platforms that must be state-licensed and regulated to operate, Kalshi is able to offer wagers on sporting events under a federal license and regulations, without the obligation to comply with each state’s policies or pay state taxes. In court, the company argues that its event contracts are legally defined as financial products, but it advertises them as wagering.

It can — and does — operate in states where sports betting is not legal.

“What Kalshi has done is sort of circumvented all of that [state regulating],” Sporttrade CEO and founder Alex Kane told InGame.

After Kalshi began offering wagers on sporting events, New Jersey, Nevada, and Maryland sent cease-and-desist letters telling it to stop operating in their states. Kalshi then sued the states, arguing that it is licensed in all 50 states and has a mandate to offer equal access to its product while saying that federal law trumps state law in this case. Courts in New Jersey and Nevada have initially sided with Kalshi, denying those states an injunction to keep operating, but in Maryland, a district court judge agreed with the state, saying that Kalshi must take its platform down. But the state agreed to put its enforcement on hold until the case is resolved.

In May, Arizona joined the list of states that have sent a cease-and-desist letter to Kalshi, and in September, the Massachusetts attorney general sued Kalshi to keep it from operating in that state.

Kalshi is also in conflict with Indian Country, which has exclusivity for sports betting and gambling in some states. Three California tribes sued Kalshi and its broker Robinhood in July, claiming Kalshi’s operation of sports betting on tribal land to be illegal, and a Wisconsin tribe followed suit in August.

Kane agrees with Kalshi’s claim that what it offers is not sports wagering, explaining that while it may look like sports betting on the outside, it is a wholly different product on the inside.

In contrast to traditional sportsbooks where users must place a bet based on the odds provided and play against the house, in a prediction market model like Kalshi or Sporttrade (in some jurisdictions), bettors can choose how much of a share or how many shares to buy and they generally play against each other. Consumers are setting the price themselves and thus usually are trading with each other rather than betting against the operator as in the against-the-house model.

Customers can buy a share in “yes” or “no” on if they predict an event will happen or not. The event might relate to something in their own lives, like “Will any Covid vaccine lose its FDA approval this year?”

“We want to have a market for anything that’s in the news,” Mansour said. “The vision is, I think this should be able to rival the stock market one day.”

Said Kane, “We feel the exchange concept is so much better for consumers, and potentially I think it’s likely possible Kalshi’s going to be successful in creating this sort of national construct for this very specific, niche market-based form of trading.”

The exchange aspect of it all is another topic of debate, and that is due to the participation of liquidity providers. At Kalshi, that includes Susquehanna International Group as well as Kalshi Trading, where both Mansour and Lopes Lara are board members. In effect, a group affiliated with Kalshi and its principals is participating on Kalshi’s own exchange, which creates concerns about possible conflicts of interest and insider trading.

State regulation is expensive for sportsbooks and includes application and licensing fees, state-specific compliance departments, and tax rates. Tax rates vary by state with the highest levied by New York and New Hampshire at 51%, while Illinois has a progressive rate that may exceed 51% for some. Sportsbooks are also required to provide responsible gambling tools and sometimes pay for market-access deals.

Kalshi makes its money through commissions on every contract bought or sold on its platform, as well as a fee on debit card deposits and withdrawals, according to Forbes.

Although Mansour is more interested in the market itself, the consumers dictate the market, and sporting events are what’s trending. “I think he views sports as yet another application of prediction markets,” Kane said.

Sports has been available on Kalshi for less than a year, and Kane estimates it’s already 70-90% of its volume. In Week 1 of the NFL season, Kalshi did $303 million in volume, and 84% of that came from contracts on football games. In total, 96% of Kalshi’s volume for the same week was from sports-related event contracts.

What makes Kalshi unique

The word kalshi means “everything” in Arabic, Mansour’s native language. The company says it is unique because it literally does offer trading on everything, from traditional betting topics like sports and finance to out-of-the-box topics like culture, politics, and science. Customers can go to Kalshi’s website and buy prediction shares in questions like “Will OpenAI release a social app this year?” and “Who will headline the Pro Football Championship halftime show?” all in one place.

Mansour saw a demand for a market for everyday people who might not follow sports or the stock market but would find use in a similar product where they can bet on topics they know.

“My brain naturally fits with that view of the world, which is that I try to price everything,” Mansour said to Sourcery.

While Mansour’s vision sounds ambitious, fulfillment seems possible given the amount Kalshi has grown since its regulation in 2020, and even just this year.

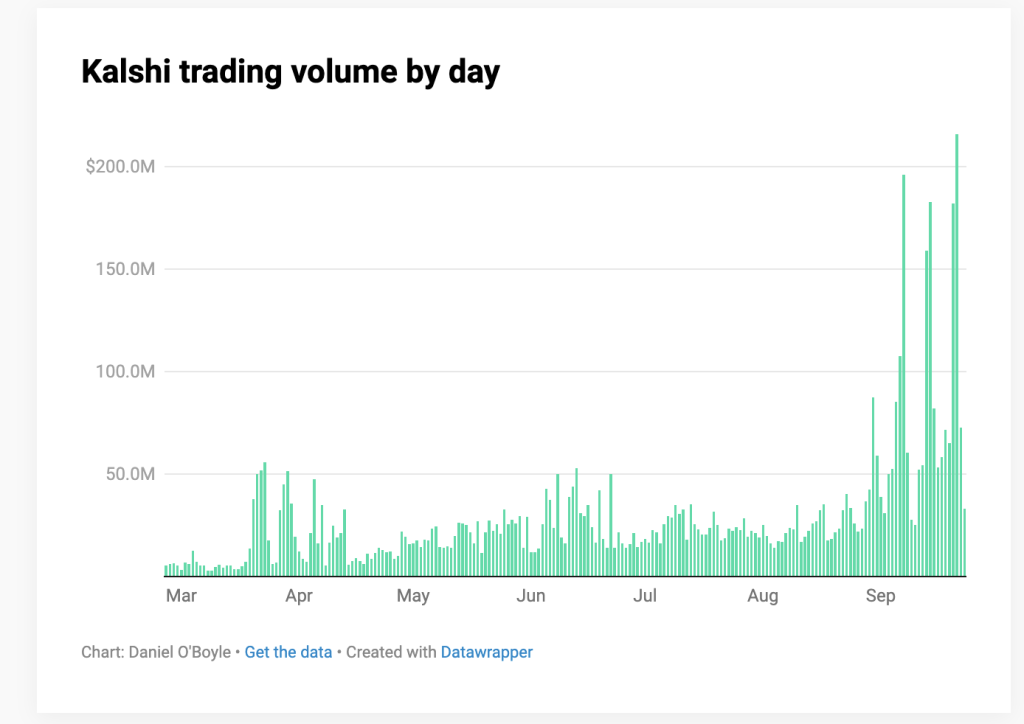

Until late March, Kalshi customers traded less than $10 million worth of contracts per day, but the exchange has grown rapidly in the past six months. On Sept. 21, Kalshi had its biggest day since it launched sports event contracts at $216 million in trading volume.

Users have traded more than $6 billion worth of contracts this year, with almost a third of that activity in September alone.

Besides that, Kalshi is becoming more and more mainstream. On Sept. 25, the company, along with competitor Polymarket, made its way onto an episode of pop-culture television favorite South Park. The company and Mansour tweeted at least seven times about the episode … and also offered prediction markets on it.

Kane described Mansour as cunning, aggressive, and smart.

“I think smart business people don’t always tell what they’re thinking. They’d rather listen than speak, and understand and ask questions,” Kane said. “Less so in the mood to overshare about his plans and Kalshi’s plans and more trying to do some recon on us and others.”

Mansour on social media

Kalshi gained even more attention in 2024 when it won a lawsuit against the CFTC that allowed it to offer election contracts. The agency at first blocked Kalshi from offering election bets in 2023, then Kalshi took the risk of suing the government and according to Mansour, unpredictably won. Customers flocked to Kalshi, buying shares on Donald Trump or Biden.

When asked by Fortune about his own prediction for the presidential election outcome, Mansour said, “You don’t need to ask that question anymore. That’s the whole point.” Sure enough, the market was correct in its prediction of Trump’s victory in 2024.

“They are definitely trying to change the paradigm a little bit,” Milbank’s Sterling said. “It started out with elections, which they were vindicated in that being correct. And it’s gone on in other areas. I think it’s kind of a great American success story.”

Mansour views prediction markets as a way to follow the news and events relevant to everyone. “The message was always getting lost with mainstream media,” Mansour said to Sourcery. “Prediction markets are a way to use the wisdom of the crowds for what is going to happen.”

However, Mansour’s take on prediction markets hasn’t been entirely popular, and on social media he isn’t shy about stating his case.

On Reddit, Mansour created an “Ask Me Anything!” post regarding trading on elections. “We’ve also seen a lot of misinformation floating around about prediction markets and Kalshi itself, so I wanted to hop on Reddit to answer any questions you guys have!” Mansour wrote.

The responses he got were largely criticisms, with users asking Mansour about the morality of betting on elections.

Although Mansour continues to receive negative feedback, he remains active on social media and committed to his takes.

Kalshi faces criticism and as its profile and valuation grow, as well as its potential to upend state-sponsored markets around sports in particular, the legal and moral scrutiny will only grow as well.

Meanwhile, the platform is widely popular, with thousands of people betting every week and more on the way as additional products and marketing waves roll out. It’s clear Mansour believes in his idea and has shown he’ll work hard to move Kalshi forward against the headwinds.

In response to Kalshi introducing player props in all 50 states — another recent controversial move — Mansour wrote on X, “We keep marching.”