Crypto.com has become the first prediction market to stop offering sports event contracts in a single state, doing so in Nevada Monday, while Kalshi has asked a federal court to stand by its original decision to allow Kalshi’s contracts to remain available in the state, rather than using the Crypto.com decision as reason to also ban Kalshi’s contracts.

Last month, the U.S. District Court for the District of Nevada denied Crypto.com an injunction that would have allowed the crypto exchange to keep offering sports event contracts in the state. Absent an injunction, the contracts are effectively banned in the state.

Crypto.com says it will appeal the decision, but that appeal has not yet been filed.

Last week, the Nevada Gaming Control Board (NGCB) revealed that Crypto.com will take down its sports event contracts in Nevada Monday.

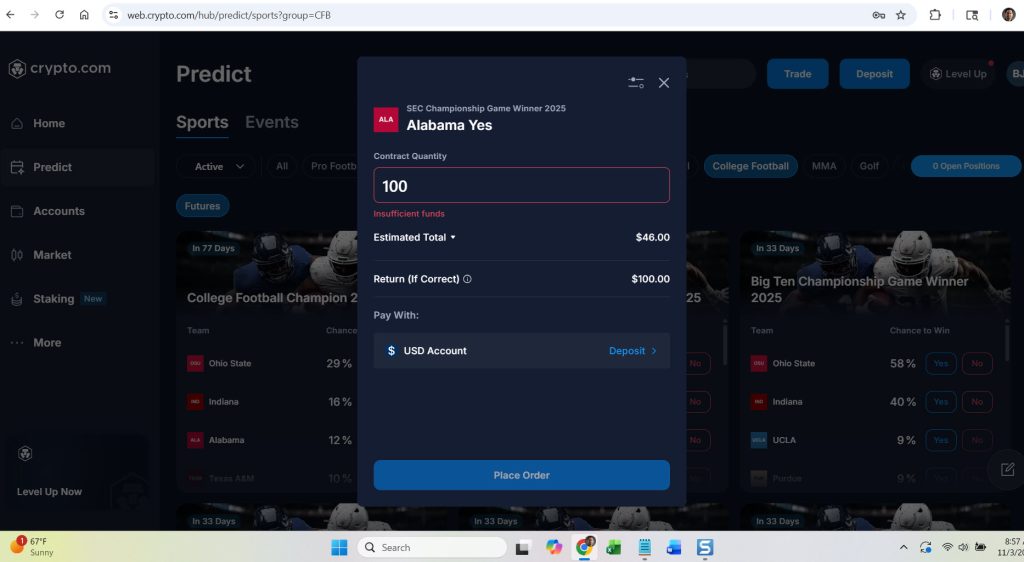

As of Monday, the contracts are not visible on the Crypto.com app in the state.

On the exchange’s website, however, the contracts are still visible, but when InGame attempted to place a bet, an “insufficient funds” error message appeared despite the account having enough funds to make the bet.

Crypto decision could affect Kalshi

The decision by Judge Andrew P. Gordon not to grant an injunction to Crypto.com may have an impact on Kalshi, as Gordon granted a similar injunction to Kalshi in a case against the state in April. Gordon did not offer an explanation for why the rulings in the Kalshi and Crypto.com cases should be different.

Gordon is also the judge in the Kalshi case.

Given the Crypto.com ruling, Nevada argued that Kalshi’s injunction should be dissolved.

Late on Friday, Kalshi filed a request not to dissolve the injunction. It argued that the motion to dissolve filed by the state was “procedurally improper and lacks substantive merit.”

Kalshi-response-to-dissolve“If Defendants believe they are entitled to judgment as a matter of law, the proper way to pursue that relief is not via a second bite at the PI [preliminary injunction] apple, but rather a motion for summary judgment,” Kalshi’s lawyers wrote.

Kalshi had previously called for summary judgment, as it argues the case can be decided based only on legal matters, without the need for discovery of evidence. The court had previously rejected Kalshi’s motion for summary judgment.

Are sports event contracts ‘swaps’?

The Crypto.com decision mostly focused on the question of whether sports event contracts are swaps — a form of financial instrument usually used for hedging risk — and regulated by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). Kalshi argues that the CFTC has “exclusive jurisdiction” over its contracts because they are swaps, while Nevada has argued that they do not meet the definition of a swap and therefore the CFTC’s exclusive jurisdiction does not apply.

According to the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA), a swap includes “any agreement, contract, or transaction … that is dependent on the occurrence, nonoccurrence, or the extent of the occurrence of an event or contingency associated with a potential financial, economic, or commercial consequence.”

Prediction markets have generally argued that this definition is wide reaching enough to cover almost any type of bet, including event contracts on sports, as long as the CFTC believes them to be within the public interest.

In the Crypto.com case, though, Gordon opted for a narrower definition. He pointed to the fact that the definition in the CEA uses both the words “event” and “occurrence,” which he says suggests that Congress intended those two words to have different meanings.

In Gordon’s view, an event is “a happening of some significance that took place or will take place, in a certain location, during a particular interval of time,” and therefore includes a sports event actually taking place, but does not include the winner of an event itself.

“An ordinary American interpreting the word ‘event’ would conclude that the Kentucky Derby is an event,” Gordon wrote. “But who wins the Kentucky Derby is an outcome of that event, not a separate event in and of itself.”

In its most recent motion, Kalshi argued that this definition was not accurate or workable.

“Dictionaries and common usage confirm that the terms ‘event’ and ‘contingency’ comfortably encompass outcomes,” Kalshi’s lawyers wrote. “A contrary conclusion would make the definition of swap — and the CFTC’s jurisdiction — rise and fall from contract to contract based on semantics, as almost any event could be characterized as merely the outcome of some other event.”

Kalshi says no change in facts or law

Kalshi also said that there hadn’t been a “substantial change in the facts or the law,” which is the typical standard to dissolve an injunction.

“Defendants cite this Court’s decision in Crypto and a decision by the District of Maryland denying Kalshi a PI in another matter. But those decisions are non-final, non-binding, and do not change any law. Defendants cite no case dissolving a PI based on such non-binding precedent. Cases finding a ‘significant change’ typically involve a new statute … or new authoritative precedent.”

Andrew Kim, partner at Goodwin Law, says that the question of whether there’s been a change in the law or the facts will be crucial in deciding the injunction. He added that the fact the Crypto.com and Kalshi cases share a judge makes the situation unusual, but does not necessarily mean that the Crypto.com decision acts as precedent for the Kalshi one.

“The question isn’t necessarily who’s right on the merits, but whether there’s been some change in the law or the facts that warrants getting rid of the injunction,” he told InGame.

“Kalshi argues that the Crypto.com decision isn’t a change in the law, because the decision doesn’t have binding or precedential effect — even if it is by Judge Gordon. (A decision by one district court judge is not binding on another judge in the same district, although the situation is a bit unusual here given that it’s a decision by the same judge on substantially similar facts.)

“Kalshi also points out that Nevada could have raised the same issues that Judge Gordon did in the Crypto.com case (the occurrence vs. outcome distinction), but it didn’t.”

Kalshi: Sue the CFTC, not us

In addition, Kalshi argued that the question of whether its contracts are swaps is one that should be addressed by challenging the CFTC under the Administrative Procedure Act, rather than by suing Kalshi.

“Federal courts may determine the meaning of the terms of the CEA, including the term ‘swap.’ The point is not that the CFTC alone is authorized to determine what qualifies as a swap, but rather that a challenge to the CFTC’s determination must be brought against the CFTC itself in a decision that will ensure the CFTC regulates uniformly nationwide — not through threats to criminally prosecute DCMs for offering event contracts that the CFTC, exercising exclusive jurisdiction, has permitted.”

Kalshi also pointed to statements by the CFTC referring to swaps as being based on “the outcome” of an event.

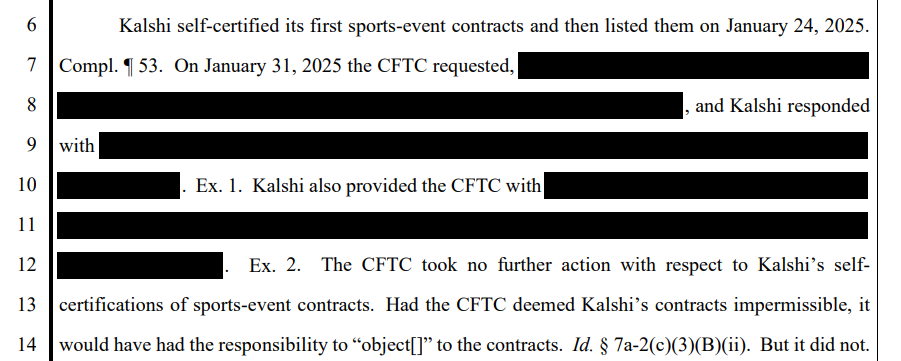

A redacted section of the filing also suggests Kalshi is providing the court with more information about the behind-the-scenes process of Kalshi self-certifying its sports event contracts, in an apparent effort to prove that the CFTC made a conscious decision not to block the contracts.

A letter to the CFTC was also filed as an exhibit under seal.

The decision by Crypto.com to take down its contracts in one state appeared to contradict an argument that Kalshi had made in the past — that a CFTC-registered designated contract market (DCM) is not allowed to block certain states from accessing its contracts.

Robinhood — which is registered as a futures commission merchant rather than as a DCM, and offers access to Kalshi contracts — had taken down sports event contracts in Nevada, New Jersey, and Maryland in the past, but no actual exchange, which makes its own contracts, had done so.

‘Impartial access’?

In cases in Maryland and New Jersey, Kalshi had pointed to CFTC “impartial access” rules, which it said meant that contracts must be available in all 50 states, or none at all.

In its motion not to dissolve, Kalshi doesn’t address the impartial access rule at all. The phrase does not appear in Kalshi’s filing.

Kalshi also suggested that if the injunction is dissolved, it will appeal the decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. The prediction market said that if court is inclined to dissolve the injunction, it should stay its decision to do so pending appeal.

Kalshi, Robinhood want CA case dismissed

Arguing that the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act does not apply to its offerings in Indian Country, Kalshi and Robinhood Friday filed briefs in Blue Lake Rancheria et al v. KALSHI INC. et al, requesting the case be dismissed. Three tribes sued Kalshi in U.S. district court in San Francisco in July, saying they want the prediction markets banned from their lands.

Writing that the tribes are responding with “overheated rhetoric” and are “calling the everyday business activities of Kalshi and Robinhood a criminal racket,” Kalshi’s lawyers wrote that the tribes have “no foothold” in IGRA as they “attempt to regulate trading on an exchange operated from thousands of miles away.”

IGRA affords compacted gaming tribes the right to regulate gaming on their lands, and in some states, traditional sports betting operators have been geofenced off reservations so that a tribe’s partner has a monopoly. In California, gaming tribes have exclusivity for gaming on their lands, per their compacts. Should the court find in favor of the tribes in this case, it could create a domino effect in which gaming tribes across the U.S. ask to be geofenced out.

A key issue in this case is the question of whether or not the Commodities Exchange Act (CEA) or IGRA, both federal laws, take precedence. Kalshi clearly argues that the CEA takes precedence.

In prediction market cases against states, so far three judges — one each in Maryland, Nevada, and New York — have directed a prediction market to stop operating. But regulators in Maryland and New York have agreed not to enforce the order until the cases have been resolved.

At an Oct. 24 hearing, Judge Jacqueline Corley strongly suggested that Kalshi and Robinhood reconsider why they are pushing to operate where they are not wanted. She has not yet issued a decision on the tribes’ ask for a preliminary injunction, and oral arguments in the case are set for March 19, 2026.

Brian Joseph and Jill Dorson contributed to this report